Dr Humaira Qaderi is a writer and women’s rights activist. She was a teenager during the years of the Taliban, when girls were forbidden from going to school and libraries were closed. Qaderi read whatever she could find and attended underground women’s writing classes, at great risk to her family and herself. Today, alongside her writing and activism, Qaderi is a university professor and senior advisor to the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

Have your rights ever been violated?

During the time of the Taliban, the Herat Society of Teachers for Literary Theory, a male-only literary circle, heard rumours I was a writer and decided to read my stories at one of their gatherings. As a woman I couldn’t attend, let alone present my stories, so one of the men read them on my behalf. Eventually, a collection of my stories was published – the first collection of stories written by a woman to be published under Taliban rule. I’ll never forget how stressed and worried my father was that day, how scared he was. He tried to buy all the newspapers in the city so that no-one would know I existed. It would be extremely dangerous for me and my family if people knew.

What do you see as an achievement in Afghanistan?

It is possible now to change the mentality of men in Afghanistan. But for me, the most important change since the time of the Taliban is the way I understand my own power. I am different now, and I can stand more firmly in combating discrimination against women. Women are strong now: their strength has forced men to abandon the Taliban mentality. No community and no woman in Afghanistan would tolerate the rule of the Taliban again.

What are the most notable changes since the time of Taliban rule?

I call this time ‘the era of awareness’. There is a new perspective in Afghanistan, and at the heart of it is awareness. This awareness is palpable throughout the entire country, from big cities to small villages, which once were dominated by the Taliban. The inhabitants of these cities and villages now want their kids to go school, something that was not possible under Taliban rule.

What do you fear?

My biggest fear is that, God forbid, some political parties will form alliances with the Taliban and re-introduce them to the political sphere. These are the games of politics – they are extremely dangerous games.

What are the major challenges facing Afghanistan?

The success of the new era of governance in Afghanistan depends critically on the active and conscious participation of women in social processes. This has always been a great challenge throughout the history of our country.

Ethnic division poses another major challenge. Instead of developing a sense of nationhood and working on nation building in Afghanistan, the emphasis has always been on ethnicity and tribalism. We also face an economic challenge: Afghanistan still lacks an independent and working economy.

Is it possible that girls could once again be banned from schools and women excluded from the social sphere?

I am afraid that the dirty political games could lead to a return to the past. Maybe the exclusion of women will not be as strong and pervasive as it used to be, but there is a risk it could re-emerge to some degree. This is a particular risk in the Taliban-friendly regions. But the young girls I know today will resist the return of such outdated ways of thinking.

Which factors hinder women’s participation in social, economic, political and cultural arenas?

The first and the biggest problems come from tradition. There are those who support the oppressive traditions towards women in the socio-political structure of Afghanistan.

Another major impediment is women’s economic dependence, which forces Afghan women to live under harsh circumstances and suffer ruthless crimes.

The incorrect interpretation of religion, and arbitrary religious practices, are further obstacles to women’s participation. The absence of reformist religious leaders has made it possible for certain groups to monopolise religion in Afghanistan.

What are the demands of the women of Afghanistan?

The dominant masculine interpretations of Islam need re-thinking. Our economic model must be restructured and revised, so that women’s labour is fully recognized and supported. And the social, political, economic and cultural structures in Afghanistan, dominated by and oriented towards men, should be transformed into merit-based structures, which guarantee justice, personal security, and the right to work for women.

Which social forces can women count on?

I can rely only on my own capacity and abilities. There is no other institution or structure in which I can take refuge.

How have you overcome obstacles?

In the almost fifteen years that I have been a writer, I have always focused on women. Everything I have written is fighting for equality. I have had reason to rebel – for equality, not for dominance.

Any final messages you wish to share with the world?

During the reign of the Taliban, I had two close girl friends: Lida and Shakiba. Lida could have been a great poet, but she couldn’t bear the inequalities of our society. She killed herself by self-immolation. Shakiba did the same. Many were waiting for me, the third corner of the triangle, to burn myself. I remember my little brother asking me once, “When are you going to burn yourself”? Losing my friends was painful, but it also taught me a lesson and made me strong.

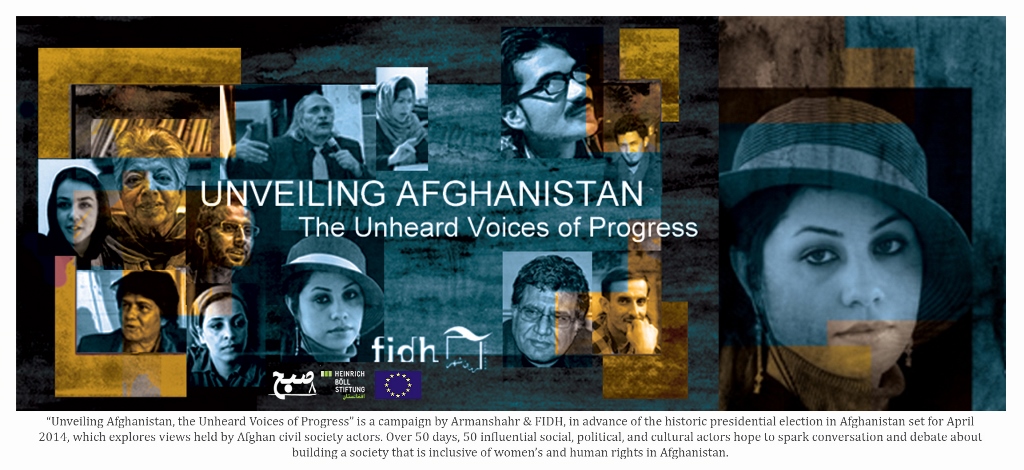

“Unveiling Afghanistan, the Unheard Voices of Progress” is a campaign by Armanshahrand FIDH, which explores views held by Afghan civil society actors. Over 50 days, 50 influential social, political, and cultural actors hope to spark conversation and debate about building a society that is inclusive of women’s and human rights in Afghanistan.

Follow 50 interviews drawn from the “Unveiling Afghanistan campaign” daily on the Huffington Post.

Follow Unveiling Afghanistan on FIDH Twitter: www.twitter.com/fidh_en