Qantara – In Germany, refugees from Syria, Iraq and Yemen may end up living next door to compatriots who were on the other side in the civil war. How can those who have fled their homeland also leave its conflicts behind them? Susanne Kaiser presents the project “Remembered Future”

He cared for the injured as bombs were falling on Aleppo. The young doctor was thrown into prison for his pains: among the wounded were opponents of the Assad regime and treating them is considered high treason in Syria. For five months, he was interrogated and tortured there, for five months his family didn’t know what had happened to him. After his release, he left everything behind and fled to Germany via Turkey.

In Germany he encountered people who had, like him, witnessed the horrors of war. For example an engineer from Iraq whose younger brother was shot dead by the IS in Mosul. Back in Iraq, the young man had been very pious and the way he viewed many of the conflicts was coloured by his religious faith. Today, he sees religious fanaticism as the biggest problem in his homeland.

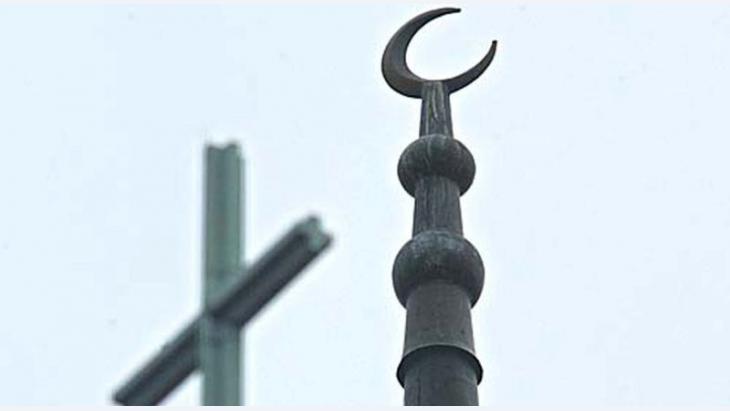

But how can these two men leave their harrowing experiences behind them? How can they distance themselves from the strife in their home region? These are the questions they are addressing together as part of a project initiated by the Catholic Academy. The idea is to bring people together from different religious communities who were once enemies in the religious wars in their home countries.

Shared memories

“Remembered Future” is what the Catholic Academy calls its project. It is based on the idea that religion should be understood not only as part of the problem, but also as part of a solution. Participants are thus reminded of the common heritage of Christianity and Islam, of Shia and of Sunni Islam – and also of the long stretches of history in which different faiths co-existed peacefully alongside and with one another.

The Middle East in fact looks back on a rich tradition of interfaith relations. The Muslim Abbasid caliphs between the 8th and 13th centuries, for example, cultivated a strong culture of theological debate between Muslims and the Christians who were also at home in their empire. Greek philosophy also figured in the Islamic theology of the period.

But there are much more recent examples of the peaceful co-existence of communities of diverse faiths. In Syria, for instance, Christians and Muslims lived side by side in harmony up to a few years ago. New forms of a common religious practice were even in the works.

At the Syrian Catholic monastery of Mar Musa, the Jesuit priest Paolo Dall’Oglio – guided by a “love of Muslims and Islam” – dedicated himself to a dialogue with Islam and developed new ways of linking the Christian and Muslim traditions. Sectarian confrontations between Sunnis and Shia were also few and far between prior to the outbreak of the Syrian civil war.

These are the interwoven historical threads that the project “Remembered Future” takes up. The hope is that by emphasising a common heritage, the potential for reconciliation between the various religions will come to the fore and thus a step can be taken away from what separates people and towards what unites them. Remembering the peaceful co-existence that once was should help to shape the future of the Middle East.

Dialogue rather than confrontation

This is a future that also begins here in Germany, with people who will eventually return to their home countries. At the moment they are still living in our midst, which means that Germany also needs to search for ways to make peaceful co-existence possible. This concerns not only the sectarian conflicts amongst refugees themselves, but also co-existence between refugees and those who settled in Germany several decades ago. According to representatives from the Catholic Academy, we must overcome the deep rifts between religious communities and denominations resulting from conflicts in the region as soon as possible if we are to prevent them from affecting life in this country.

With this in mind, the Catholic Academy has turned to established methods of interfaith dialogue – a form of engagement that has contributed to reconciliation in other serious crises taking place in diverse parts of the world. Under the leadership of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, for instance, South Africa′s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was charged with working through the crimes committed under apartheid. With an even hand, it addressed violence perpetrated by South Africans at all levels of society, regardless of their creed or ethnicity.

The idea was to convince both the victims and the perpetrators to enter into a dialogue and thus lay the groundwork for the reconciliation of the warring groups. The focus thereby shifted from confrontation to helping both sides to see how the others perceived things.

Marvelling at and arguing about religious diversity

Germany has in fact not always been the oasis of diversity and peaceful co-existence it might appear to be today to civil war refugees arriving from the Middle East. The history of a divided Germany is still very present. The war experiences of the refugees can thus be embedded in a larger context. Parallels between cities like Berlin and Middle Eastern towns like Aleppo and Mosul are perhaps not plain at first glance, but they can be uncovered with the history of Germany’s division in mind.

One of the issues the participants thus discuss in the project work is the Berlin Wall. It stands for a similar history of flight, of divided neighbourhoods and families torn apart. East Germany was once a police state like Syria or Iraq. And yet people managed to overcome this chapter of German and European history, to bring down the wall. A reunited Germany was the result.

Berlin is a glowing example: the German capital tells a story of religious diversity and ethnic plurality. People with different backgrounds and beliefs live together in close proximity. Most of the time, all goes smoothly. In Berlin, a Sunni mosque, a Bulgarian Orthodox church built on the site of a former Protestant cemetery, a mosque of the Ahmadiyya movement and a Danish Lutheran church, not to mention a Russian Orthodox community are all located at a stone′s throw from one another.

Even the city’s museums can teach us a thing or two about the shared history of Christians and Muslims: refugees who have fled the Middle East and recently found a new home in Germany cherish the material aspects of culture that bear witness to this proximity of the religions. At the same time, the relations between Europe and the Middle East become evident on an entirely different level, because the historical cultural heritage exhibited in Western museums consists of objects whose rightful ownership raises some uncomfortable questions. Do these treasures belong to the respective German museum or to the people from whose civilisation the artworks were once taken? This kind of marvelling and arguing about religious diversity both current and past is also part of the project.

When the wars in the Middle East come to an end and the refugees are able to return home, they will carry with them this message of reconciliation and pass it on – this, at least, is the hope of the project’s initiators. Remote from the grand scheme of geopolitics, the project “Remembered Future” strives to make a difference at the modest level of everyday co-existence. Every bit of success, no matter how small, could have a major impact on the future – both here in Germany and in the Middle East.

Susanne Kaiser

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor