Armanshahr Foundation in collaboration with the French Institute of Afghanistan, in support of Coalition for Peace Campaign 2011, Afghanistan Civil Society Network for Peace and Afghanistan Transitional Justice Coordination Group is pleased to invite you to its 82nd (year VI) public debate GOFTEGU on the occasion of International UN Days for Peace and Mobilization against war and occupations

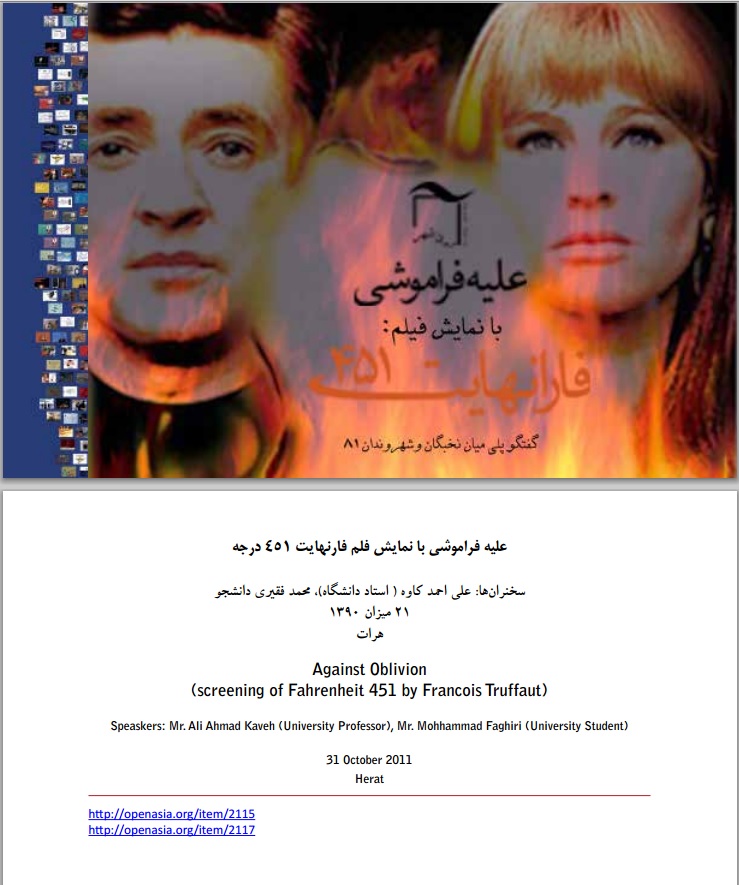

Against Oblivion

Screening of Fahrenheit 451 by François Truffaut

Speaker: M. Partaw Naderi (Poet)

Moderator: Seyed Jawad Darwaziyan

Date et Horaire/Date & Time:

Mercredi/Wednesday 19 OCT. 2011, 14:00 H.

Lieu/Venue: Institut français d’Afghanistan/French Institute of Afghanistan

Tel: 0779217755 & 0775321697

E-mail: armanshahrfoundation.openasia@gmail.com

http://armanshahropenasia.wordpress.com

(Film in English with Dari subtitles-Debate in Dari)

Book burning and wiping out collective memory – against oblivion

The 82nd (6th year) Goftegu, a bridge between the elite and the citizens, of Armanshahr Foundation, was held in cooperation with the French Cultural Institute of Kabul in the Institute on 19th October 2011 with the title of “Against Oblivion.” The speaker was Master Partow Naderi, who gave a moving account of book burning in the Afghanistan Writers Association under the Taleban. After his speech, Fahrenheit 451, the film made by the French director François Truffaut, was screened.

The film had been chosen, because it portrayed methods of wiping out collective memory by burning books and controlling the public opinion on the one hand, and the people’s resistance and disobedience on the other, where the people burned among their own books but save them to defend the human experience and collective memory.

The 82nd Public Debate was initially scheduled for 22 September 2011, but it was postponed for security reasons, because it coincided with the burial of Burhanuddin Rabbani, chair of the High Council of Peace.

At the time, we wrote to our guests: “Why was the Goftegu debate postponed until further notice? The reason is clear, when the oppressed people are set on fire every day, the explosion of bombs, the sound of bullets and the roaring of tanks and planes wreak havoc in this country; fighting based on ethnic, religious, lingual and regional differences increases.”

Fortunately, we managed to hold the debate later and 110 citizens, mostly students, attended the meeting.

Rooholamin Amini was the moderator of the meeting, who opened it with a poem from Kazem Kazemi and then invited MasterPartow Naderi, veteran poet, writer and journalist, to address the meeting.

MasterPartow Naderi made a reference to the history of Afghanistan in the past three decades and said:

Afghanistan lost many cultural and human values during those three decades. As an employee of the Afghanistan Writers Association (AWA), after the fall of Dr Najibullah, I bore witness to those bitter events.

The AWA had published about 270 titles in Persian, Pashto, Uzbek and English with print-run ranging from 1,500 to 3,000. Most of those books went into heating stoves.

The AWA was not the only institution that lost its books. The huge Hakim Naser Khosrow Balkhi Library in the city of Puli Khumri was ransacked under the Taleban. I was working for the BBC at the time and I asked Mullah Motmaen, the then spokesman of the Taleban, about the burning of thousands of books in that library. He answered: The 50,000 books you are referring to have not been burnt. Any book that propagates things against national unity or the Ismailia must be burnt.

MasterPartow Naderi continued to recite his poetic text: Finally, the gun-totters conquered the office of the AWA president… The office was turned into a bedroom for one of the commanders and his cohorts. There was a large desk in that office, which had been converted into a bed for the commander and somebody would sleep on it in daytime. When the winter arrived, a stove was placed next to the desk. It had an audacious open mouth; it was the strangest stove. It read books, day and night, not line by line, but chapter by chapter and volume by volume. It had an open mouth and reached only three conclusions at the end of each book: heat, smoke and ashes. Books by literary and historical giants sighed and screamed in fire, called for help, but there was nobody to come to their rescue…

At the back gate of the AWA’s bookshop, there was a rather tall young man who was talking noisily, but not in an angry tone, with the people around him. He had thick eyebrows and a piercing look, wearing a camouflage jacket; he gave small gifts to the people around him. A few weeks before, they had conquered the office of Žwandun magazine. I guessed that he must be one of the commanders. I was right. I found out later that his name was commander Ashiqullah or Mashuqullah. I went closer and greeted him. Before saying anything else, I caught a glimpse of the bookshop. The books had fallen from the shelves on the floor and the commander and his cohorts were using the AWA’s bookshop as a shortcut exit. They had stamped the books with their steps. You could see the trace of their feet on each book, as though they had issued orders to annihilate culture and spirituality.

The commander’s mouth smelled of home-made wine. I asked him: why do you burn these books? It is a sin. The commander answered: we burn the books that do not bear ‘bismillah’. I have ordered my soldiers to separate the books that do bear it. At the time, scholars in Pakistan sought to buy each of those books at several times their real prices, but they couldn’t find them.

The 1980s were a decade full of big disasters, but those years constitute a considerable era in the contemporary history as far as promotion of books and culture of reading is concerned. For example, the books published by the AWA were far more numerous than those published in 100 years in the whole of Afghanistan.

To view the publications related to this Goftegu Public Debate, please refer to the following links:

Invitation to 82nd Goftegu Public Debate: Against Oblivion -2