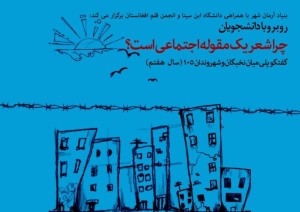

Armanshahr Foundation in collaboration with Ibn Sina University and PEN Afghanistan, has the pleasure to invite you to its 105th (Year VII) public dialogue GOFETGU

“Human beings are members of a whole” (Saadi of Shiraz)

Why is poetry a social issue?

Debate and Poetry reading with: Professor Ali Amiri (Ibn Sina University writer of Sleep of Reason),

Ms. Khaleda Forugh (Poetess, researcher, producer of literary programme Kakh-e Boland on Tolo TV),

Aman Pooyamak (Poet and writer winner of Simorgh Peace Award and Nowruz literary Prize),

Yassin Negah (Poet, writer and Director of Porsesh weekly)

Moderator: Rooholamin Amini (Poet, writer and Deputy director of Armanshahr Foundation)

DATE and TIME: Thursday 28 march 2013 at 14H.

PLACE: Ibn Sina University, Karteh 3, Across from Omarjan Kandahari Mosque

CONTACT: 0787195212/ armanshahrfoundation.openasia@gmail.com

SITE: http://openasia.org

ATTENTION! KINDLY CARRY ORIGINAL OR COPY OF THIS INVITATION.

This programme is organised by Armanshahr with the financial assistance of the European Commission However it can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of above-mentioned institution.

Armanshahr is a member of the FIDH.

Why is poetry a social issue?

In commemoration of 21 March, World Poetry Day, and the ancient Nowruz, the 105th Goftegu (Year VII) public debate of Armanshahr was held with the title of “Why is poetry a social issue?” at the Ibn Sina University’s hall, in cooperation with Ibn Sina University and PEN Afghanistan on 30 March 2013. The meeting was addressed by Professor Ali Amiri (Ibn Sina University and author of Sleep of Reason), Mohammad Yassin Negah (poet, writer and director of Porsesh weekly) and Aman Pooyamak (poet and writer, winner of Simorgh Peace Award) and a number of poets recited their poems. More than 150 men and women, students and academics participated at the meeting, which was covered by the various media.

The moderator, Rooholamin Amini, opened then meeting with the following words: “Our culture is inundated with poetry and not just poetry, but poetry anthologies. The most important reference points are poems in philosophy, social critique and political critique.”

Then, Professor Ali Amiri said: “It is open to question if poetry is a social issue. This question has taken the social nature of poetry for granted, but that is not a decided matter. The question is what is poetry and why is it poetry? If we answer that question, we can clarify poetry’s relationship with other social phenomena such as philosophy and mysticism. This is a hypothesis that has not been proved.

“By an old definition, poetry is imaginary. That is why Plato banished poets from his utopia. It has been accepted in logic that poetry is rooted in imagination and not in reality; poets deal with imagination and not with reality.

“As far as the tradition of the Persian language is concerned, ideas such as human rights, civil and political rights, protest and the like do not exist in our history. They entered the arena of social issues after the onset of constitutionalism.”

Commenting on Mr Amiri’s presentation, Mr Amini said: “Given the status of poetry in our culture, we always think of the past when the talk of poetry. Nevertheless, the modern literature is also part of the Persian literature and we have Shamlou, Akhavan, Forough, Vasif Bakhtari and others. Some of these people used poetry as a means of political struggle, e.g. Ahmad Shamlou. Furthermore, poetry of Hafiz is full of critiques of Sufis, inquisitors and mullahs who had social and even political power, and therefore critiquing them was a social action.”

Mohammad Yassin Negah, the second speaker, argued: “There is no text outside the society. It is the tendency of the Creator that categorises literary texts to social and non-social types. Sartre is of the opinion that there is a bilateral relationship between literature and the society. Literature is the shelter of the oppressed, and the poor. The writer has the freedom to have political or social commitment.

“I believe that the Persian poetry has been based on commitment from the beginning. Unfortunately, nowadays I’m not optimistic. Most writers, who approached the issues with scepticism, were either shunned from the society, their books were taken off the shelves or they faced other restrictions. That means we cannot be sceptics. It is a crime to think here. However, when you deprive a writer of thinking, they will have nothing left and they’d better report for a medium. We need a critical realistic literature to criticise the contradictions in the society, to stand up against inequalities.”

Mr Aman Pooyamak argued that social poetry must go through the social and intellectual channels. Discussing the weakness of our S, he said: “In Afghanistan, we have not yet been able to identify the doctrines that underlined the poetry of such poets as Saadi and Hafiz. On the other hand, more has been written about them in the West. The present-day Western can be easily found in our own literature, which is full of human advice. We can deduct social contracts from them and suggest them to the West.”

In conclusion, a number of poets who had come to the meeting from different parts of the country, recited their poems, including Khaleda Forough, Kaveh Jobran, Sohrat Sirat, Wahid Warasta, Asar-al-Haq Hakimi, Farhard Azimi Fada and Mohammad Aref Kanfuda.