Special to The Globe and Mail

Published Friday, Oct. 25 2013

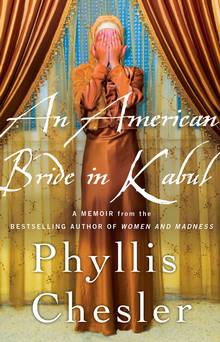

Title: An American Bride in Kabul

Author: Phyllis Chesler

Genre: nonFiction

Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan

Pages: 256

“I once lived in a harem in Afghanistan” is the gripping opening sentence of An American Bride in Kabul, in which feminist academic and native New Yorker Phyllis Chesler recounts her experience of 50 years ago as an imprisoned Afghan wife. Memoir is only a thread in this expansive work: life in purdah, confined within the harem of an immensely wealthy Afghan family, spurred Chesler to a lifetime of research and activism on behalf of women in the Islamic world. Much of the book is structured as a dialogue between East and West, in the ongoing exchanges between Chesler and her Afghan ex-husband Abdul-Kareem, who have preserved their unlikely and complex connection through the decades.

When Chesler was an 18-year-old college student in New York in 1959, she met and fell in love with foreign student Abdul-Kareem, son of one of the wealthiest men in Afghanistan at that time. Chesler’s characteristic dry humour permeates the narrative as she relates the germination of their romance, as does her penchant to refer to sources (the bibliography at the end of this book is eight pages long):

“True, he is a Muslim and I am a Jew. … But he is Agha Khan, and I am Rita Hayworth. He is Yul Brynner, and I am Gertrude Lawrence in The King and I.

“Years later, I would learn that this beloved musical is based on the chilling diary of Anna H. Leonowens. Entitled Siamese Harem Life, it documents the slavery, cruelty, and other practices that are considered customary in the East.

“Unfortunately I fall in love before I find this extraordinary volume.”

Chesler is self-mocking as she relates her youthful desire for adventure, and how this undoubtedly factored into her decision, at 20, to consent to Abdul-Kareem’s urging that they marry, travel to Europe and live temporarily with his family in Kabul. Once there, Chesler is made to surrender her American passport, which she never sees again. Soon she finds out that the “temporary” stay in Kabul is meant to be a permanent life change; that she is now an Afghan wife with no rights as an American, even according to the U.S. embassy. Her father-in-law has three wives, though only the youngest and most fertile is still treated as a wife.

By far the biggest shock for Chesler is that Abdul-Kareem, her courtly, worldly husband and partner of several years, has overnight become a stranger whose behaviour ranges from unsympathetic to physically abusive. This holds true even when Chesler becomes seriously ill with hepatitis – Abdul-Kareem’s central concern remains his standing in Afghan society, which his American wife is endangering with her failure to conform and submit.

What may be most remarkable about An American Bride in Kabul is that it is not a condemnation of Islam, nor is it a personal vendetta against Abdul-Kareem. Instead, even while acknowledging the emotional trauma that surrounds her months in Kabul, Chesler unravels the layers of her experience with ruthless intellectual precision. She sees her marriage to Abdul-Kareem as having been doomed from the start – not just because of his culture, but because of her own Western-born desire for independence. Through the lens of her observations and accompanying research, Chesler presents a fascinating, compassionate portrait of an Afghan family, thereby creating a thesis for what she sees as the inherent dangers to women in some of the Islamic world. This thesis is tempered with an abiding respect for many customs in Eastern culture and love of Abdul-Kareem’s family, with whom she still celebrates weddings and other family functions (they immigrated to America in the late 1970s).

Respect and compassion are to a large degree what make the narrative so compelling: Chesler presents Abdul-Kareem as a tortured man, torn by the inimical forces of his Eastern heritage and the Western values with which he sympathizes. Chesler points out that for Abdul-Kareem to bring home a Jewish wife from America signified an enormous, brave rebellion against his family; that subsequently there was equally enormous pressure on him to demonstrate that he had not abandoned his heritage, or risk being cut off financially and emotionally from his family forever. On the other hand, she is critical of his denial of the existence of honour killings, a subject which Chesler has researched and written about in depth in the past decade.

An especially haunting figure is Bebegul, Abdul-Kareem’s mother and his father’s first wife. Most women in Chesler’s position would be eager to present Bebegul in as negative a light as possible – and with justification: Bebegul harassed and abused Chesler throughout her stay in Kabul. But instead Chesler looks back on the life Bebegul must have had, and how even this wealthy woman of privilege is an archetype for the suffering of women in Afghanistan. Discarded by her husband as a penalty for an alleged impropriety, confined to the home without any social outlet, Bebegul is insane by the time she encounters the 20-year-old Chesler. It may be due to Bebegul that Chesler would eventually write Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, which details the horrors women in oppressive cultures visit upon each other as retribution for their own suffering.

With its sharp critique of honor killings, polygamy and purdah, with references to the burka as a “sensory deprivation chamber,” An American Bride in Kabul throws down the gauntlet to Western feminists who refuse to condemn these practices. It is a challenge that is at the very least worth hearing.

Ilana Teitelbaum is a writer living in New York.