By MARGHERITA STANCATI in Kabul and RACHEL PANNETT in Makassar, Indonesia

More than 590,000 Afghans had been displaced by fighting and Taliban threats by late August.

Thousands of Afghans have fled their homes for refugee camps in and around Kabul. Many are hoping to get asylum in Australia and elsewhere.

Wazira, a 37-year-old mother of six, abandoned her home and apple orchard in Afghanistan’s rural Wardak province last year and moved with her whole family into a single room on the fringes of the Afghan capital.

“We didn’t have any choice but to come to Kabul,” she says. “The Taliban were forcing us to prepare food for them. But if we did, the government would harass us. We were stuck in the middle.”

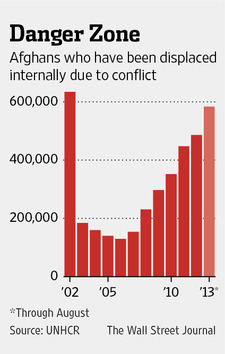

More than 590,000 Afghans had been displaced from their homes by fighting and Taliban threats by late August, according to the United Nations, a 21% increase since January and more than four times the number in 2006, when the insurgency began in earnest. Wazira, who like many Afghans goes by one name, is one of more than 12,000 displaced people from Wardak province alone who now share homes around Kabul, according to the U.N.

More than 590,000 Afghans had been displaced from their homes by fighting and Taliban threats by late August, according to the United Nations, a 21% increase since January and more than four times the number in 2006, when the insurgency began in earnest. Wazira, who like many Afghans goes by one name, is one of more than 12,000 displaced people from Wardak province alone who now share homes around Kabul, according to the U.N.

U.N. officials worry that widening violence could kick off an exodus abroad when American-led forces leave the country next year.

For those trying to leave Afghanistan altogether, the first stop often is neighboring Iran or Pakistan. Some who are wealthy or lucky enough head for Europe or Australia, which already is coping with an influx of Afghan boat people. Some 38,000 people from Afghanistan have managed to get into industrialized nations to apply for asylum last year, more than from any other country, according to the U.N., and the highest figure since the U.S. invasion in 2001.

“The desperation is incredible,” says Richard Danziger, the Afghanistan head of the International Organization for Migration, a U.N. affiliate that is helping resettle the refugees.

A confidential preliminary report drafted by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal describes a scenario that would see some 200,000 Afghan refugees fleeing to Pakistan and Iran next year.

“If we keep on the current trajectory, there will be one million displaced people over the next two or three years,” says Aidan O’Leary, the Afghanistan head of the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Sabir Shah is trying to reach Australia but has gotten no farther than a hotel in Indonesia, where he has been for months. Rachel Pannett

Afghanistan’s displacement and refugee problem stretches back over three decades of warfare. The number of displaced Afghans and asylum seekers initially peaked in 2001 when the Taliban government was toppled, then declined during the first few years of the U.S.-backed government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai. But as the insurgency gained momentum from 2007, the numbers rapidly climbed.

Afghan troops are sustaining record casualties this year in the fight against the resurgent Taliban. Many Afghans are worried that the security situation will deteriorate sharply next year, as the U.S. completes its withdrawal and an election to choose President Karzai’s successor fuels political instability.

“We are expecting emigration to increase,” says Jamahir Anwari, Afghanistan’s minister of refugees, whose own family is split between Turkey and Sweden. “This worries us.”

Faced with a rising tide of displaced people, the Afghan government recently drafted a policy to help resettle them inside the country, which is awaiting cabinet approval.

A U.S. government official familiar with the issue said: “We are concerned about levels of internal displacement.…Providing humanitarian assistance to this displaced population is a priority, and remains challenging because of high levels of insecurity.”

Many Afghans caught in the crossfire between government and Taliban forces leave behind everything when they flee their villages. The situation is especially bad in the district of Sayedabad, a battlefield on a crucial highway between Kandahar and Kabul.

That is the region from which Wazira, the mother of six, fled. Her home and orchard had sustained damage from heavy fighting. “We are scared,” she says. “The Taliban told us that if we went to Kabul, we wouldn’t be able to go back.”

That is the region from which Wazira, the mother of six, fled. Her home and orchard had sustained damage from heavy fighting. “We are scared,” she says. “The Taliban told us that if we went to Kabul, we wouldn’t be able to go back.”

Some of the displaced say the violence there is as bad as it has been since the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979. “I’ve lived through decades of war and never left my village,” says a 70-year-old tribal elder who fled his home and now lives on the outskirts of Kabul. “If there’s security, I won’t stay in Kabul for one more hour.”

There are few good prospects for occupants of the displaced persons’ camps and informal settlements ringing Kabul and other relatively safe Afghan cities. Many are hatching plans to get out of the country.

Pakistan and Iran are often steppingstones for journeys to Europe or Australia.

The bulk of Afghan migrants aim for Western Europe, according to U.N. data. Last year, about 7,500 Afghans applied for asylum in Germany, followed by Sweden, which received 4,750 applications, and Turkey, which got 4,400. Only 204 Afghans applied for asylum in the U.S.

Australia is regarded by many Afghans as a land of especially good opportunity. The number of Afghan refugees showing up on Australian beaches hit 4,256 last year, up from 118 in 2008, according to the Australian government.

“In our village, people are mainly talking about Australia: Who reached it from our village? Who sent money from Australia? How is the route?” says Ali Shah, a 60-year-old baker from the Muqur district in Ghazni province, a Taliban stronghold.

Last year, Mr. Shah fled his home with 10 family members. “Muqur is not safe,” he says. “The Taliban run their own government. They control checkpoints and administer justice.” Mr. Shah is now jobless and living in a different district. His 25-year-old son, Sabir, left Afghanistan this spring, hoping to reach Australia.

The journey to Australia often begins with a smuggler in Kabul. One such operative, who uses the name Hadi, told a Journal reporter that he charges up to $10,500 for visa and travel to Indonesia. It would cost another $5,000 to attempt to reach Australia by boat, he said. The cost means that many would-be migrants are, by Afghan standards, relatively affluent, such as small-business owners.

Many who head for Australia, including Mr. Shah’s son, belong to the ethnic Hazara minority that has been persecuted by the Taliban, and that has the most to lose should the Taliban return to power after the American withdrawal.

“All the people are worried about what will happen after 2014, and so are the Hazaras,” says Afghan Hazara leader Mohammed Mohaqeq, who is running for vice president in next year’s national elections. He survived an assassination attempt in June. “Security is getting worse everywhere,” he says.

Hayatullah Saadat, 28, an English-speaking management graduate from an Indian university, says he hopes to get to Australia next spring, by boat if necessary. “I came back from India and thought: ‘I have to help Afghanistan,’ ” he says. “But then I lost hope. Nobody is sure about their income. Nobody is sure about their life.”

The journey to Australia typically takes refugees through Pakistan or India, then Malaysia and Indonesia. Some have died on the last leg when the Indonesian fishing boats they were traveling in sank.

After Australia tightened its immigration policy, many refugees now are stranded in Malaysia and Indonesia. Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s conservative coalition, elected in September, is promising to use the Australian Navy to intercept and forcibly return refugee boats to other countries’ waters. His predecessor, Kevin Rudd, had instituted a policy to remove asylum-seekers to poorer countries such as Papua New Guinea to be processed and resettled there.

As a result, the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, which has long served as the starting point for the sea crossing to Australia, is becoming packed with Afghans. Some 80 refugees are living in the dilapidated Mahkota Hotel in the Sulawesi town of Makassar, one of scores of rundown residences filled with Afghans. The International Organization for Migration is paying for the housing.

Sabir Shah, the son of the displaced baker from Muqur, made it to the Mahkota Hotel. He left Kabul carrying a small bag with pair of jeans and a shirt, a traditional Afghan outfit, a shaver and a mobile phone. He flew to Malaysia on a fake student visa in early May, after paying a smuggler the first half of an $8,000 fee.

“There was a fear of Taliban,” he says. “Almost every day we heard that a Hazara interpreter or schoolteacher had been killed by Taliban.”

He traveled from Malaysia to Indonesia’s Sumatra island on a wooden fishing boat one night with about 20 Afghans. The crossing was rough. He has been at the Mahkota Hotel for months, awaiting a chance to resettle in Australia or elsewhere. He spends his time studying English and working out at a local gym.

Jawad Heidari, 29, a resident of the same hotel, says he sold a second-hand-car dealership in Kabul and his Toyota Lexus luxury sedan to raise $36,000 for a smuggler to transport him, his wife and two sons.

A former customs officer, he says he fled Afghanistan in April after receiving Taliban threats. “I would do anything to get to Australia,” he said recently from a dingy hotel room.

Nearby, Afghan women fried eggs over a camp stove to augment food deliveries from the international aid organizations. A group of girls played with Barbie dolls on the narrow balcony.

Samrin is one of the girls at the Mahkota Hotel. Her father, Noor Ahmad, entered Australia as a refugee in June after more than two years in immigration detention in Indonesia and two failed attempts to reach Australia by boat.

“After 12 days in the sea, our boat encountered a storm,” recalled Mr. Ahmad, a Hazara from Ghazni province, from his new home in Dandenong, a migrant suburb in Australia’s second-largest city, Melbourne. “Everyone was scared and we had no hope anyone would survive.”

His wife, Zeba Ahmad, 24, and daughter Samrin set out seven months ago to join him, but remain in limbo at the hotel in Indonesia. Every time Samrin sees a plane in the sky, her mother says, she asks whether it will take her to her father.

—Ehsanullah Amiri and Habib Khan Totakhil in Kabul contributed to this article.

Write to Margherita Stancati at margherita.stancati@wsj.com and Rachel Pannett at rachel.pannett@wsj.com