Source: HBS

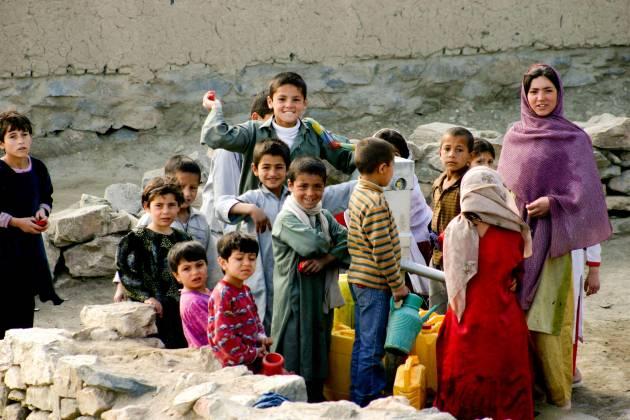

Mobility has long been a survival strategy for many Afghans during the past decades of conflict and economic uncertainty. This article discusses the impact of a deteriorating security situation, international security transitions, a faltering economy and declining international assistance, and the demographic stress of rapid population growth and urbanization on the two-thirds of the Afghan population under the age of 25 – Afghanistan’s youth. It suggests that the most viable coping strategy for young Afghans may once again be to leave their homes in search for a better future.

The overall positive spirit around the 2014 Afghan presidential elections, an important transition from Hamid Karzai who has ruled since 2002, has led to new uncertainties for the country’s population due to allegations of election fraud, a lengthy audit process and the inability of the two lead candidates to come to an agreement. How this political transition plays out will affect socio-politics, security and peace, feeding trends that are already in motion. The continuous deterioration of the security situation and the foreign withdrawal set to be complete by the end of the year have added to the growing crisis.

Young adults in Afghanistan, in rural and urban areas alike, have grown up with a collective unease and the worry that the coming decade will mirror the previous. The hope that was prevalent in the early years of the Karzai administration has gradually diminished and the outlook of many adolescents for the years ahead holds little promise. Many feel increasingly that their future lies elsewhere, because progress has been too slow, and Afghanistan is still very much behind even poor neighboring countries. It would therefore not be surprising if it came to another displacement crisis in a country where mobility has long been a major coping mechanism of a war-plagued population. This paper discusses the current push factors for displacement in Afghanistan, as well as facilitating factors and migration paths.

Displacement trends – going, going, gone again

Internal displacement has been on the rise in Afghanistan. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), nearly 700,000 individuals had left their homes in mid-2014, half of whom had been displaced over the past three years[1]. Though no longer in first place, Afghanistan is also among the top three countries of origin for asylum seekers worldwide (75,273 in 63 countries, with Turkey and Germany being the top two recipient countries). Many Afghans arrive as unaccompanied minors, particularly boys under the age of 18.

These confirmed figures are likely just the tip of the iceberg, with UNHCR acknowledging that it does not have the means of recording displacement in insecure areas, and that it only recently started to grapple with profiling and counting urban displaced populations. These figures also do not include those displaced by natural disasters. The only reason we might not see as large an external displacement as in the past is that traditional exit options (Iran and Pakistan) are no longer as attractive, and many Western states have established stronger barriers for would-be refugees. This has forced Afghans to either displace internally or use more creative ways of reaching a safe haven abroad. Those with resources have already begun to move their families to Dubai (figures are sketchy, but since 2010 an estimated 6.9 billion US Dollar was transferred from Afghanistan to Dubai in cash alone and around 300,000 Afghans are estimated to live there).

Officially, around 10,000 Afghans are currently studying abroad (half in India, the rest in Pakistan, Europe, North America and Australia) and possibly as many as 3.4 million live and work abroad undocumented or in temporary work arrangements (all but 400,000 in Iran and Pakistan)[2]. Marriage to exiled Afghans with dual nationality or reunification with relatives in the West has also become a popular exit option. “Afghans who can afford to will pay as much as 24,000 US Dollar for European travel documents and up to 40,000 US Dollar for Canadian. (Visas to the United States, generally, cannot be bought.).”

By far the biggest flow of people, however, is into major Afghan urban centers. Currently there are about 7.2 million urban dwellers in Afghanistan (30 percent of the population), with at least 2.2 million of them having arrived in the past few years (about half from rural areas and half refugee returnees), though actual figures could be higher[3].

The push: Why people are on the move once again

Afghanistan has made major, albeit uneven, progress since 2001, with high economic growth, improvements in social indicators and investment in government institutions and infrastructure. In contrast, there has been weaker performance in agriculture and urban development and governance has been deteriorating. A former development minister recently suggested it might take the country ten more years just to reach least-developed status[4]. This is a sobering reality after so many aid dollars were spent. Prevailing insecurity is usually one of the key drivers of displacement and thus a fairly good indicator or predictor for future population movements.

The recent spike in violence in Afghanistan does not provide much confidence that conflict-induced displacement will diminish any time soon. In 2013, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) recorded a 14 percent increase in civilian casualties from the year before[5]. In the first six months of 2014, UNAMA documented 4,853 civilian casualties (1,564 civilian deaths and 3,289 injured) – 4,600 in the first quarter alone [6] – accounting for a 24 percent increase in civilian casualties compared to the first six months of 2013 [7].

A new trend, however, is that deaths and injuries due to ground engagement and cross-fire between Afghan national security forces and anti-government forces are surpassing those caused by improvised explosive devices, indicative of the spreading fighting [8]. Human Rights Watch warns: “The ability of Afghan security forces to hold government-held territory, let alone retake insurgent-controlled areas, is unclear, and security concerns for much of the population remain high.”

This trend has persisted for several years. A 2010 poll by three news agencies found that only roughly half of Afghans felt adequately protected from the Taliban and other armed groups, a share essentially unchanged from the previous year [9]. In 2013, another opinion poll reported that a majority of Afghans feared for their own safety or that of their family, and that they were afraid when travelling within the country. The choices of civilians living in areas that are contested or controlled by antigovernment elements are limited: stay and acquiesce, leave to government-controlled major urban areas, or be killed.

Wide-spread injustice and impunity

Added to insecurity is the failure of the Afghan government to protect its citizens from predatory behavior. In a recent study by the Liaison Office, a majority of those interviewed listed as a main grievance the failure of the Afghan government to provide rule of law and equal justice for all, and to hold those in power, including government officials, accountable for abusing their positions [10]. A carpet dealer from Mazar-e Sharif sums up what many think: “Punishment is for those who do not have power. But for those who have power or have links to powerful persons, there are rewards and not punishment.”[11]

A majority of respondents also believe the government does not respect rights enshrined in the constitution. Several studies have pointed to the fact that especially in rural areas, 70–80 percent of conflicts are resolved informally, as many feel that the formal justice sector, rather than protecting them, violates their rights through extortion [12]. The complaints are widespread: non-prosecution of corrupt officials, impunity of strongmen, failure to assist the poor. While registering some progress, Afghanistan’s security apparatus continues to falter in the face of armed opposition and has been unable or unwilling to protect civilian populations adequately. Elements within the force, especially the Afghan Local Police, have been credibly accused of widespread human rights violations [13].

Corruption has been consistently identified as one of Afghanistan’s most serious problems, “ahead even of poverty, external influence and the performance of the Government” according to a 2013 UN survey, a finding also supported by other opinion polls [14]. The Kabul Bank scandal and the failure of the government to address it weighed especially heavy on the Afghan psyche, given the sheer scale of the fraud and its ties to the elite. Many see the government as dominated by self-serving politicians. In the words of a female teacher from Herat: “They are busy with their luxury lives and forgot about us. There is no one to listen to us.” [15]

Uneven quality of key service delivery

Despite significant progress in the delivery of basic services (such as education, health care and roads) across the country, arrangements remain uneven at best in quality and reach. There has been minimal improvement on the Millennium Development Goals, and Afghanistan still ranks below the average of countries in the low human development group (175 of 187). Women are often worse off than their husbands or brothers, with Afghanistan’s Gender Inequality Index – reflecting disparities in reproductive health, empowerment, and economic activity – ranking the country next to last (147 of 148).

Many Afghans feel they can only obtain services from the state if they have contacts, and there is mention of widespread nepotism and clientelism. Though education is often used as a success story, a 2011 study by the Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief (ACBAR) criticized that the focus had been on quantity and not quality. While student numbers have increased, their literacy levels have not; a 12th year graduate might not be able to read or write properly [16].

The ACBAR study also critiqued the quality of health care, with the World Health Organization describing Afghanistan’s health status as one of the worst in the world, with inequality in access being a significant problem. This makes for pitiful health statistics: One in ten children will not live to start primary school, and one Afghan woman dies every two hours due to complications during pregnancy. Although generally urban areas in Afghanistan are better off when it comes to access to key services,30 service delivery and government policy has not yet caught up with the challenges of growing urban poverty, especially food security [17].

As a result, a majority of the Afghan population is unhappy about the imbalance between the resources and money poured into Afghanistan’s administration since 2001 and the lack of quality of service delivery, often citing experiences in exile as a reference point for what could be better. Thus, those who can afford it may attend the growing sector of private educational institutions or try to obtain a coveted scholarship to study abroad. Others spend entire family fortunes in travelling to Pakistan or India – some even to the West – for treatment unavailable in Afghanistan.

Lack of economic growth, livelihoods and employment

In contrast to population growth, economic activity appears modest at best. The after-effects of violence across the country, especially in Kabul, have caused anxiety to rise and consumer confidence to plunge. Uncertainty over the transition is only compounding this trend. However, Afghanistan’s dependence on international assistance – and an illicit drug economy – does not provide for a sustainable future. With the departure of the foreign military, a great deal of international assistance will also dry up. The recently-released National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment found that unemployment and underemployment is high, especially for women, youth, and rural populations.

The share of the working population in vulnerable employment – own-account workers, day laborers and unpaid family workers – is 81 percent (79 percent for men and 87 percent for women) [18]. Compared to men, female work is much more concentrated in just a few sectors, particularly in livestock tending and food processing. The anxiety of an increasingly young and also more educated population vis-à-vis their future is acutely felt when speaking to them: Nearly eight in ten name unemployment as one of their greatest problems, followed by underemployment. The opportunities for many young Afghans are slim: remain and stay unemployed or underemployed (in lieu of joining pro-government or anti-government armed groups), go abroad for (mostly illegal) work, or attempt to make it to the West.

Factors facilitating out-migration

Return has been less sustainable than hoped: Despite initially hailing the Afghan return story (over five million) as a success, the UNHCR is the first to admit that return has been unsustainable for many – if not a majority – due to the struggle to obtain a place to live and make a living, let alone access basic services and security and protection. Many returnees live in secondary displacement, unable to go home, or have left again in search for employment, security and basic services such as health care and education. This has made displacement protracted and durable solutions difficult to find.

Demographic stress – the young and restless in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is currently facing the classic dilemma of least developed countries: chronic underdevelopment, weak economy, rapid population growth and swift urbanization (too swift for service delivery to keep pace). Those under the age of 25 make up nearly two-third of the Afghan population, which is estimated at around 30 million [19]. This means greater competition for resources such as land, services and employment in a country struggling to provide for its current population. Simple math will tell us that the larger a population, the greater the pool of future displacement. It also means more demand for education, both basic and higher.

Afghanistan is a country that has historically excluded youth (and also women) from key decision-making by focusing power in the hands of older male elites. The 2013 draft Afghan National Youth Policy (ANYP), for example, chose to define youth within the Afghan context as “a person who is between the age of 18 and 30.” [20].For some young adults, these attitudes can shut them out of the adult world until an age where many in other countries may have already begun successful careers.

Some analysts suggest that a society unable to absorb new generations is more conflict-prone than others. Anti-government groups in Afghanistan, but also progovernment militia, are getting increasingly young; “There aren’t many suicide bombers over 20 years old.” Past displacement experience and a widespread diaspora is helpful in weighing options. This would not be the first time Afghans have been displaced in recent history.

In fact, it has been the norm: about three in four Afghans have experienced forced displacement at some point in their lifetime. Most Afghans have an exit strategy, and many no longer have the strong connection to their land and livelihood that would once have kept them there. Having spread their risk during past displacement, extended families are often dispersed across numerous countries, increasing the destination options. Unlike those in Pakistan and Iran, refugees who travelled further have often obtained citizenship in their new homes. Family reunifications or marriages of in-country and diaspora Afghans have occurred in the past and are likely to increase as they provide tickets out that bypass lengthy asylum procedures and rejections. Furthermore, migration research has shown that the existence of diasporas always lowers the threshold for out-migration, as a path has been established and a support network exists.

Where will people go? New migration pathways

Knowing where people are likely to go would help to focus assistance and prevent subsequent displacement. With traditional exit options increasingly difficult (Pakistan insecure and impatient, Iran simply impatient), and new ones usually demanding a considerable access to resources (financial or educational), displacement will likely be concentrated internally.

- The rush on Afghan cities:

Kabul is considered “one of the fastest growing cities in the region” [21], expanding three-fold over the past six years to a population of more than five million; other cities are also expanding quickly. Government officials informally estimated that a majority of the urban population in Kabul and other major cities lives in informal settlements that house the displaced. Young people from 15 to 24 years are more numerous in urban areas, suggesting that young adults tend to be drawn to cities regardless of their families’ residence [22].Also, those families wishing an education for their daughters, or women wishing to work, will prefer urban over rural areas.

- Dubai, the new Pakistan for the Afghan elite:

Many old and new Afghan elites and the rising middle class have begun to seek out residence visas in Dubai. The new trend is for the family to be based in Dubai while the mostly male breadwinner returns to Afghanistan. This is a foot in the door for worse times to come.

- India:

The most promising education route for young Afghans, India, has become the new neighbor of choice, for study and also health care travel, for those who can afford it. Both young men and women study abroad, though more often than not young men dominate.

- The West:

This mainly involves the costly smuggling of mostly unaccompanied minors (under 18) and travel on marriage visas. As noted earlier, existing diaspora networks have facilitated legal immigration through marriage visas for both young men and women. The illegal route remains popular, however, especially for young men. While costly, a family might pool their money to give one young man a chance to make it to the West, hoping for reunification later. In this one respect, being young and male proves to be an asset.

This text is part of the latest Perspectives Asia.

Fußnoten:

[1] (1) Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, December 2013

(2) Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2013) Global Overview 2012: People internally displaced by conflict and violence (Geneva: IDMC, April 2013);http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-overview/pdf ; p. 62

[2] Koser, Khalid. Transition, Crisis and Mobility in Afghanistan: Rhetoric and Reality; Kabul: International Organization for Migration, January 2014;http://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/Country/docs/Transition-Crisis-and-Mobility-in-Afghanistan-2014.pdf

[3] National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment

2011–12. Afghanistan Living Condition Survey;

pp. 9–13

[4] Private remark to author’s colleague in late 2013

[5] Afghanistan Annual Report 2013 on the ‹Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict›; Kabul: UNAMA, 2014

[6] Integrated Regional Information Networks News, 2 April 2014

[7] Afghanistan Mid-Year Report 2014 on the ‹Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict›; Kabul: UNAMA, 2014

[8] Afghanistan Mid-Year Report 2014 on the ‹Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict›; Kabul: UNAMA, 2014

[9] Afghanistan – Where Things Stand, ABC NEWS / BBC / ARD POLL, 11 January 2010, p. 7

[10] Unpublished Study on State Legitimacy, Kabul: The Liaison Office, April 2014

[11] Male Carpet Dealer / Shopkeeper, Mazar-e Sharif, 28 March 2014.

[12] Susanne Schmeidl. 2011. «Engaging traditional justice mechanisms in Afghanistan: State-building opportunity or dangerous liaison?» pp. 149–172 in Whit Mason (Ed.) The Rule of Law in Afghanistan: Missing in Inaction. Cambridge University Press.

[13] Afghanistan Annual Report 2013 on the ‹Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict›; Kabul: UNAMA, 2014

[14] Corruption in Afghanistan: Recent Patterns and Trends – Summary Findings, December 2012, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Islamic Republic of Afghanistan High Office of Oversight and Anti-Corruption, p. 3

[15] Female Teacher, Herat City, 10 March 2014.

[16] Male Architect, 50s, Pashtun, Focus Group Discussion, Kabul, 30 March 2014

[17] National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment

2011–12. Afghanistan Living Condition Survey;

p. xvi

[18] Research Study on IDPs in urban settings – Afghanistan 2011, Susanne Schmeidl, Alexander D. Mundt and Nick Miszak, 2010, Beyond the Blanket: Towards more Effective Protection for Internally Displaced Persons in Southern Afghanistan, a Joint Report of the Brookings / Bern Project on Internal Displacement and The Liaison Office

[19] National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011–12. Afghanistan Living Condition Survey; p. xvi

[20] National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011–12. Afghanistan Living Condition Survey;

p. xvi

[21] Joe Beall and Daniel Esser, 2005, «Shaping Urban Futures: Challenges to Governing and Managing Afghan Cities.», Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit; p. 11

[22] National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011–12. Afghanistan Living Condition Survey; p. xvi