Source: ICG

The 47 Republican senators who wrote to Iranian leaders this month may have believed they were sabotaging the talks on a deal on Iran’s nuclear program, hoping it would exacerbate fears in Tehran that any such deal could be reversed by the next U.S. president.

No one knows how the talks will end, or which party will win the White House next year, but Iranian leaders most likely believe it has strengthened their negotiating position. That’s because this partisan stunt was old news when it arrived in Tehran. The Iranians were fully prepared for attempts of this sort to undermine the negotiations in which they have invested so much.

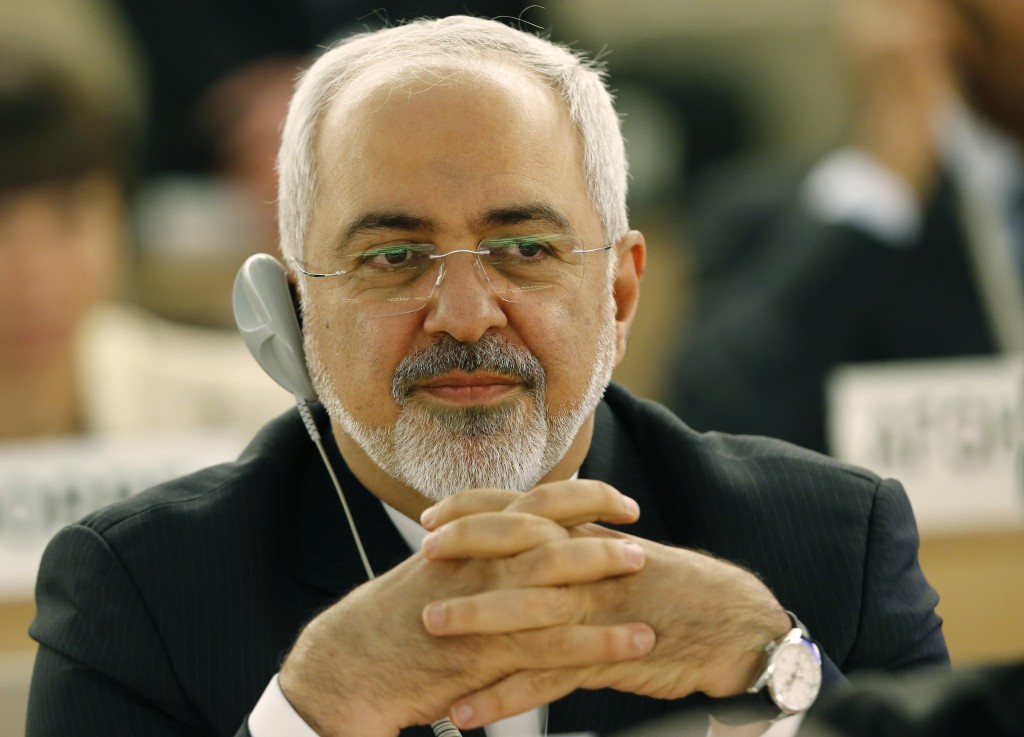

Iran’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, has spent the majority of his life in the U.S. and is intimately familiar with American politics and laws. This, combined with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s deep skepticism of U.S. intentions and trustworthiness, resulted in an Iranian negotiating strategy that has long insulated itself against the risk of Congressional upsets.

Knowing full well that Congress is unlikely to cooperate with the White House to relax U.S. sanctions, they have been aware from the beginning that all the Obama administration could realistically offer — at least in the agreement’s early stages — was suspending the sanctions by using the president’s waiver authority.

That realization had four specific consequences for Iran’s negotiating stance. First, since suspension of sanctions is more reversible than their termination, the Iranians insist on maintaining sufficient leverage of their own in the form of thousands of centrifuges. Iran’s current operating enrichment capacity has limited practical use, since fuel for the country’s sole nuclear power plant in Bushehr is supplied by Russia. But Iranian leaders calculate that maintaining a meaningful enrichment capacity might deter the U.S. from reneging on its part of the bargain.

Secondly, instead of focusing on unilateral U.S. sanctions, the Iranian negotiators have gone after the UN Security Council sanctions that legitimize the American ones. The logic is that if the next U.S. president revokes the nuclear deal and tries to re-impose sanctions without the legitimacy bestowed by the UN, he/she will have a much harder time rallying international support behind enforcing the restrictions.

Thirdly, Iranian negotiators demand that a roadmap for lifting the U.S. sanctions during the agreement must be codified by a UN Security Council resolution. This would make any American infringement of it a breach of an obligation under international law. They have, moreover, indicated they intend to make the Iranian parliament’s ratification of the Additional Protocol to the Nonproliferation Treaty that provides the UN inspectors with enhanced access to nuclear sites and scientists contingent on prior legislative action in U.S. Congress to terminate some specific sanctions.

Finally, based on the supreme leader’s instructions, the Iranian negotiators are trying to tie up all ambiguities in the agreement to ensure that no aspect will be open to interpretation. Moreover, just as Washington insists on a role for the International Atomic Energy Agency to monitor Iran’s implementation of its commitments, Tehran insists on establishing a mechanism to monitor Washington’s performance on sanctions relief.

Seen from Tehran, therefore, the letter has strengthened Iran’s negotiating position. It also gives Tehran an edge in any blame-game that would inevitably follow a still-possible failure to reach a comprehensive accord. It will now be much easier to portray U.S. demands as excessive and maximalist than it was before the letter, and before Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to Congress last week.

The Iranians also appear to know perfectly well that by further alienating the Congressional Democrats, the letter makes any future attempt to pass deal-killing legislation more likely to fall short of garnering sufficient support in the Senate to override an Obama veto.

The Senate Republicans appear to have unintentionally miscalculated. Underlying their missive is an assumption that Iran somehow is a far-away place, unknown and untrustworthy, easy to use as a U.S. domestic political football. Senators may indeed feel nothing in common with Iran.

But Iran’s leaders spend every working day examining every move of the country that has done so much to cut them off from the rest of the world for the past 35 years. Letters or no letters, they thus appear to be well aware, as Ayatollah Khamenei suggested, that “governments are bound to their commitments by international laws and would not violate their obligations with a change of government.”

The Senators have thus not just handed the Iranians a rhetorical victory. They have also shown themselves less than Iran’s equal in their ability to understand their adversary.