Source: Aljazeera

Meerut, India – The massacre took place on May 22, 1987, the last Friday of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

The families of Hashimpura – a predominantly Muslim locality in the city of Meerut, 75km northeast of New Delhi in the state of Uttar Pradesh – had retreated to their homes to break fast.

Dusk transformed into night in relative peace – until armed officers started charging into homes, rounding up as many able-bodied men as they could.

“They burst inside the house, went inside, upstairs, everywhere shouting, ‘Where are your men, where are your men?'” Zapun Begum told Al Jazeera from the courtyard of her home, her eyes cast downward.

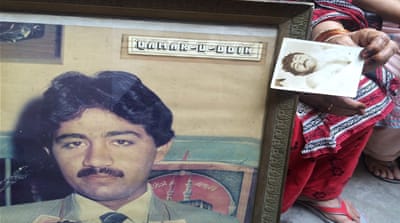

A framed wedding portrait of her then-22-year-old son, Qamar-u-ddin, rested against the side of the plastic lawn chair in which she sat. In her wrinkled hands, she held a small photograph showing his body after it emerged from the river in which it was dumped: chest bare, eyes shut, body wrapped like a mummy.

Her other four sons were able to get away, but it was her eldest that received the same fate as 41 other Muslim men in what’s become known as the “Hashimpura massacre” – a 28-year-old mass murder that only reached a verdict days ago despite its age.

A New Delhi court last Saturday acquitted 16 Uttar Pradesh police personnel charged with abducting some 50 men of Hashimpura that night, driving them away in a yellow truck, shooting them, and dumping 42 bodies into the river.

Prosecutors allege the police officers were part of a state police unit called the Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC).

“It was a joint operation of the army, the local police, the PAC and the central reserve police force,” Satish Tamta, the special prosecutor appointed to the case in 2008, told Al Jazeera.

What happened that night in Meerut was an isolated incident no one anticipated. But the city had a history of communal flare-ups every few years, and that time in particular was tense.

A year earlier, then-prime minister Rajiv Gandhi opened up the gates of the Babri Masjid for Hindu worship. The site of the famous mosque, located in the Uttar Pradesh city of Ayodhya, has long been a contention for Hindus and Muslims.

Hindus say it is the birthplace of Lord Ram. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a right-wing Hindu nationalist group, had laid claims to the mosque site since the late 1970s. By the time Gandhi opened it in 1986, both communities were highly polarised on the issue.

Religious riots

Clashes between Hindus and Muslims erupted in Meerut and its surrounding areas in the days preceding the Hashimpura massacre. A curfew was put in place, along with “regular checking.”

“During communal riots, the normal practice is that people are searched and their houses are searched for any legal or illegal weapons,” said Vibhuti Narain Rai, the then-superintendent of police in neighbouring Ghaziabad district, who has written a book on the massacre.

Different law enforcement agencies collaborated to conduct the searches and arrests that night in riot-affected areas, according to the court‘s charge sheet.

“There were riots happening in Meerut, but not in Hashimpura,” Zulfiqar Nasir, one of five survivors of the massacre, told Al Jazeera.

Some allege police prejudice led to the killings.

“The PAC at that time was known as an anti-Muslim police force,” said Zafaryab Jilani, a legal advisor to the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and leader of the Babri Masjid Action Committee. “They do not come to action by themselves … The local police generally calls the PAC because its numbers are not sufficient.”

Revenge attack?

According to the English translation of the court’s charge sheet, “some unsocial elements” had attempted to murder a member of the PAC, and seized two guns from PAC officers.

A Hindu boy was also killed in the violence, leading some to believe the massacre may have been a form of revenge.

“He [the Hindu boy] was standing on the roof of his house and a bullet came from the side of Hashimpura and struck him,” the former police superintendent Rai said. “It was an understanding that he had been killed by a Muslim.”

Yet these incidents are likely to have been staged, said Paul Brass, a researcher on South Asian politics and author of the book The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India.

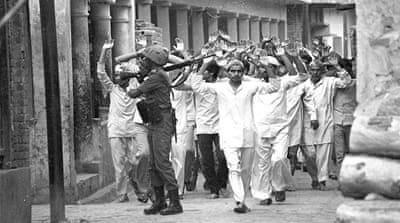

Photojournalist Praveen Jain had come to Meerut from New Delhi that day to photograph the ongoing communal riots. He instead captured the unfolding action before the Hashimpura massacre.

“They were crying and begging, ‘Leave us we are innocent,” Jain told Al Jazeera. “And the army handed over these innocent people to the PAC.”

The judge last Saturday cleared the 16 accused PAC personnel – originally 19 before three died – saying there wasn’t enough evidence to prove their responsibility for the massacre.

Defence lawyer LD Mual said the Provincial Armed Constabulary unit was made a “scapegoat” and the judgment was based upon the evidence presented in the case files.

“As far as the investigation of the case is concerned, the subject matter is with the state,” Mual told Al Jazeera.

‘Ties of the khaki’

Critics argue the handling of the investigation, which took nine years to complete, shows authorities purposefully delayed the case to protect the assailants.

The “fraternal ties of the khaki,” – police officers wear khaki uniforms – also overshadow any investigations they must do on each other, said Vrinda Grover, a victims‘ lawyer.

“Under Indian law, it is the state that is the investigating and prosecuting agency,” Grover said. “If the state is with the accused, then the exact framework in which justice should be delivered will be badly shaken.”

The holes in the two-decade-long investigation might have been explained better had the right sources been available as well, said Tamta, the special prosecutor for the case.

“Two of the major investigating officers of the case had died during the course of the trial, and so there was no one to tell the missing links to complete the story.”

Ramesh Dixit, a retired professor of political science at Lucknow University, pointed out that lawyers assigned to the case changed many times, until victims’ families petitioned for the case’s transfer to New Delhi in 2002.

“It’s the police forces, bureaucracy, and also those political personalities who just try to hush up everything,” Dixit said. “It’s a shame on the state.”

Victims’ families and survivors are now planning to appeal.

Grover said the issue must be raised outside the court as well. “There are serious issues of how the legal system is functioning and not delivering justice repeatedly in the cases of mass crimes and targeted killings,” she said.

Mohammed Qadir, whose father was killed in the massacre – his body never recovered – said the families have waited too long for answers.

“But if they [PAC] didn’t kill them, who did? It’s the state’s responsibility to tell us,” said Qadir.