By Phillipp Schulz

March 25, 2015

Over the past two decades, the international community has witnessed progressive developments regarding the judicial investigation and prosecution of crimes of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Generally, discussions on the topic suggest or assume that sexual (and gender-based) violence is something which mostly or exclusively concerns women and girls. Only recently, the issue of SGBV against men and boys has begun to be recognised. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), for example, does not restrict SGBV to women and girls only.

What is SGBV exactly?

Crimes of sexual violence can include: different forms of penetrative rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy and forced sterilisation or abortion. Crimes of sexual torture, sexual humiliation and forced nudity may likewise constitute sexual violence. Gender-based violence, in its widest sense, may be understood as persecution on the basis of gender and can include a variety of crimes.

SGBV is often described as a strategic ‘weapon of war’. Research on the topic, however, seems to show that conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence is a very diverse, complex phenomenon. That’s why trying to explain why it occurs is not an easy task. Overall, findings by Dara Cohen suggest that sexual violence during armed conflict varies widely, in its severity and form within and across different conflicts, as well as in its motivation and cause. Similarly, the information we have to date doesn’t present a clear picture as to whether conflict-related sexual violence around the world is increasing or decreasing or whether the figures remain stable.

SGVB against men

These crimes against men are often thought to be designed to humiliate and emasculate the victim, while simultaneously enhancing the perpetrator’s masculinity by asserting power and dominance. Sexual and gender-based violence against men can take on a variety of different forms, including anal and oral rape, sexual torture, castration or genital beatings and forced nudity and masturbation.

Additionally, there have been instances where men are forced to rape either other male or female members of the family or community (‘enforced rape’) or where men are forcibly made to watch female members of the family being sexually violated. These can be considered as ‘passive’ or indirect crimes of SGBV against men. While in such cases, women are clearly the physical target and victim of the sexual attack, men may be indirectly targeted as well, by demonstrating their inability to protect their families and communities.

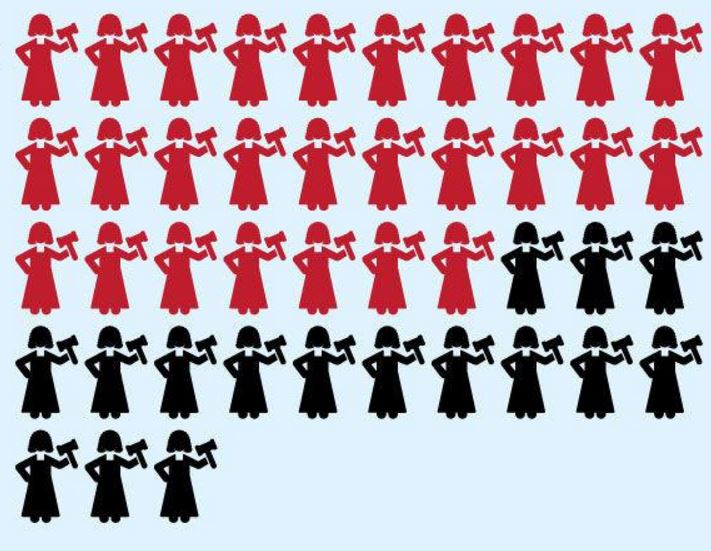

(Source for figures in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Sivakumaran (2010): Lost in Translation: UN Responses to sexual violence against men and boys in situations of armed conflict)

(Source for figures in eastern DRC: Association of Sexual Violence and Human Rights Violations With Physical and Mental Health in Territories of the Eastern DRC

Social stigma

As with female victims, the consequences for male survivors of SGBV are devastating. They affect not only the individual victim, but also their families and communities. Reports show that male victims of sexual violence are often rejected by their partners and expelled from their communities. In fact, social stigma is one of the most common consequences of sexual violence – both against women and men. This leads to vast under- or non-reporting, which in turn makes it difficult to establish the exact amount of men and boys affected by such crimes. In the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), for example, numbers vary from between six and ten per cent of male victims in one study, to 23.6 per cent in another study.

The International Criminal Court

At the International Criminal Court, prosecuting sexual and gender-based crimes is among the Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP) key strategic goals. Charges for SGBV can either be brought as crimes per se, or alternatively as forms of violence such as, for example, treating rape as torture. Additionally, acts of SGBV can be charged as different categories of crimes within the ICC’s jurisdiction and can thus constitute crimes against humanity, war crimes or may amount to genocide.

Sexual and gender-based violence may be charged as crimes against humanity when committed “as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against civilian populations”. Crimes of SGBV may also fall under the category of war crimes. All other types of war crimes may contain gender-based or / and sexual components.

(Source for the first three images: Gender Report Card)

(Source for the last image: Brigid Inder, Executive Director of Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice)

Challenges of investigating crime

Despite the overall challenges of investigating grave human rights violations committed in the context of armed conflicts, investigating and prosecuting SGBV crimes presents its own, unique challenges. The OTP identifies some of these challenges, such as the under- or non-reporting of sexual violence, social stigma facing both male and female SGBV victims, limited domestic investigations and the lack of available evidence.

Identifying and investigating crimes of sexual violence may at times also prove problematic due to euphemisms and other verbal and non-verbal communication used by witnesses or victims to describe and refer to acts of sexual violence, a challenge which is often overlooked. Additionally, investigating SGBV and interviewing victims and witnesses is closely linked to various physical and psychological challenges, which require thorough psychological assessments of witnesses and careful security screenings. Testifying in a courtroom is often emotionally and psychologically difficult for a witness.

Prosecuting the perpetrators

Regarding prosecutions and sentencing, as the experience of the ICC but also the ad-hoc international tribunals demonstrate there is often no evidence of orders to commit sexual and gendered violence. Since the ICC primarily concentrates on crimes perpetrated by those deemed ‘most responsible’, linking sexual crimes committed by soldiers or rebels to the accused with command responsibility is extremely challenging.

Despite such difficulties and challenges, however, the ICC previously has and can be expected to continue investigating and punishing SGBV committed during armed conflicts. Since the establishment of the two ad-hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and for Rwanda (ICTR), much progress has been made with regards to criminalizing sexual and gender-based violence and developing international jurisprudence. These lessons learned are of fundamental importance for the ICC’s current and future work. Despite these developments, much work still needs to be done in advancing the prosecution of SGBV crimes at the ICC, including, for example, adequate protection measures for the victims.

Lead image: Flickr/Daniel C

Philipp Schulz is a first year PhD candidate at the Transitional Justice Institute (TJI) at Ulster University in Northern Ireland, conducting research on conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence against men.