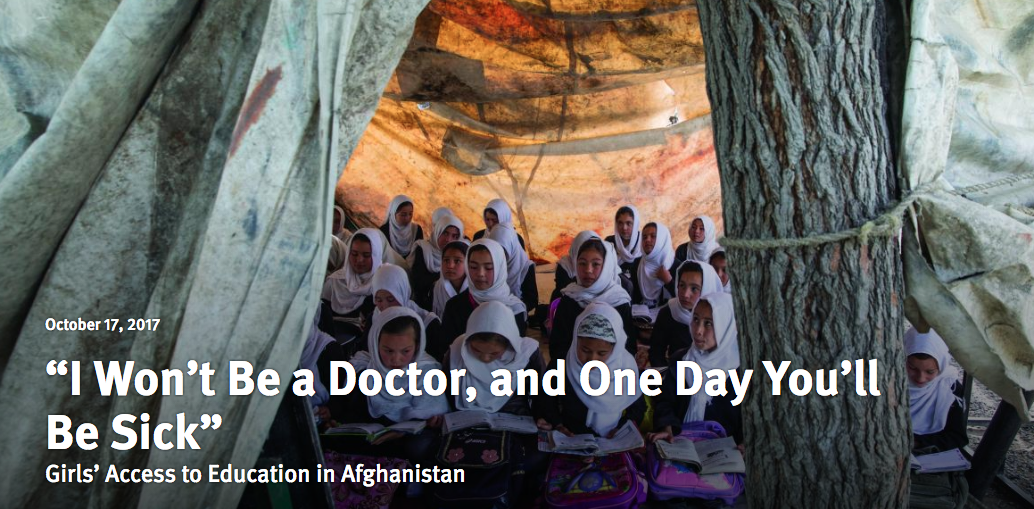

Girls study in a tent held up by a tree in a government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Forty-one percent of all schools in Afghanistan do not have buildings and even when they do, they are often overcrowded, with some children forced to study outside. © 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Girls study in a tent held up by a tree in a government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Forty-one percent of all schools in Afghanistan do not have buildings and even when they do, they are often overcrowded, with some children forced to study outside. © 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

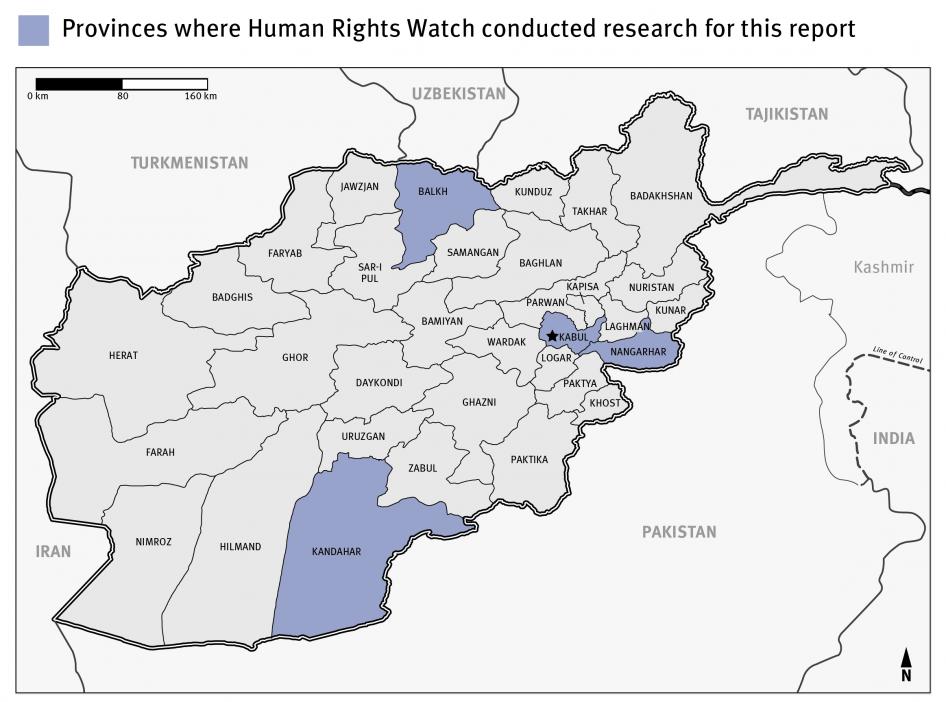

Human Rights Watch– Sixteen years after the US-led military intervention that ousted the Taliban government, an estimated two-thirds of Afghan girls do not go to school. And as security in the country has worsened, the progress that had been made toward the goal of getting all girls into school may be heading in reverse—a decline in girls’ education in Afghanistan.

Forty-one percent of all schools in Afghanistan do not have buildings. Many children live too far from the nearest school to be able to attend, which particularly affects girls. Girls are often kept at home due to harmful gender norms that do not value or permit their education.

The 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, though a direct response to the September 11 attacks on the United States, was partly framed as bringing assistance to the country’s women. Senior officials from troop-contributing nations in the early years of the war spoke out about the suffering of women under the Taliban.

Among the Taliban’s most systematic and destructive abuses against women was the denial of education. Before the Taliban came to power in 1996, Afghanistan’s education system had already been severely damaged during the country’s armed conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s. During their five-year rule, the Taliban prohibited almost all education for girls and women. So when Taliban rule collapsed in late 2001, the new government and the countries that had joined the US-led coalition faced two critical challenges: how to re-establish an education system for half the school-age population in a desperately poor country, and how to help girls and women who had been kept from getting an education during Taliban rule catch up on what they had been deprived.

The new Afghan government under then-President Hamid Karzai and its international donors approached these tasks with energy and resources. The government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), with donor support, built schools, hired and trained teachers, and reached out to girls and their families to encourage them to attend school. The actual number of girls who, over time, went to school is disputed, but there is broad agreement that since 2001 millions of girls who would not have received any education under the Taliban now have had some schooling.

But this achievement is partial and fragile. Even according to the most optimistic figures regarding girls’ participation in education, there are millions of girls who never went to school, and many more who went to school only briefly. The impressive progress the government and its donors have made in getting girls to attend school was a good beginning, not a completed task.

This report examines the major barriers that remain in the quest to get all girls into school, and keep them there through secondary school. These include: discriminatory attitudes toward girls by both government officials and community members; child marriage; insecurity and violence stemming from both the escalating conflict and from general lawlessness, including attacks on education, military use of schools, abduction and kidnapping, acid attacks, and sexual harassment; poverty and child labor; a lack of schools in many areas; poor infrastructure and lack of supplies in schools; poor quality of instruction in schools; costs associated with education; lack of teachers, especially female teachers; administrative barriers including requirements for identification and transfer letters, and restrictions on when children can enroll; a failure to institutionalize and make sustainable community-based education; and corruption.

Numbers

Statistics on the number of children in—and out of—school in Afghanistan vary significantly and are contested. Statistics of all kinds—even basic population data—are often difficult to obtain in Afghanistan and of questionable accuracy. A 2015 Afghan government report stated that more than 8 million children were in school, 39 percent of whom were girls. In December 2016, the minister of education announced that the real number of children in school was 6 million. In April 2017, a Ministry of Education official told Human Rights Watch that there are 9.3 million children in school, 39 percent of whom are girls. All of these figures are inflated by the government’s practice of counting a child as attending school until she or he has not attended for up to three years.

According to even the most optimistic statistics, the proportion of Afghan girls who are in school has never gone much above 50 percent. In January 2016 the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimated that 40 percent of all school-age children in Afghanistan do not attend school. Relying on Afghan government data from 2010-2011, UNICEF said that 66 percent of Afghan girls of lower secondary school age—12 to 15 years old—are out of school, compared to 40 percent of boys that age. In 2016, the US special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction wrote: “The MoE [Afghan Ministry of Education] acknowledged a large number of children are out of school, but is unaware of how many, who or where they are, or their backgrounds.” Donors eager to claim the success of their efforts may not be as skeptical about education statistics as they should be.

An accurate accounting of the number of girls in school matters, in part because high but inaccurate figures have given the impression that there is a continued positive trajectory when in fact deterioration is happening in at least some parts of the country. According to government statistics, while the number of children in school continued to increase through 2015, the increase has leveled off and become minimal since 2011, with only a 1 percent increase in 2015 over 2014. The World Bank reported that from 2011-12 to 2013-2014, attendance rates in lower primary school fell from 56 to 54 percent, with girls in rural areas most likely to be out of school. Government statistics indicate that in some provinces, the percentage of students who are girls is as low as 15 percent.

Analysis by the World Bank shows wide variation from province to province in the ratio of girls versus boys attending school, with the proportion of students who are girls falling in some provinces, such as Kandahar and Paktia. These disparities are mirrored in literacy statistics. In Afghanistan, only 37 percent of adolescent girls are literate, compared to 66 percent of adolescent boys. Among adult women, 19 percent are literate compared to 49 percent of adult men. Currently, as the overall security situation in the country worsens, schools close, and donors disengage, there are indications that access to education for girls in some parts of Afghanistan is in decline.

Despite the overall progress, Afghanistan’s provision of education still discriminates against women by providing fewer schools accessible to girls, and by failing to take adequate measures to remedy the disparity in educational participation between girls and boys.

Schooling in Afghanistan

The Afghan government has not taken meaningful steps toward implementing national legislation that makes education compulsory. Although by law all children are required to complete class nine, the government has neither the capacity to provide this level of education to all children nor a system to ensure that all children attend school. In practice, many children do not have any access to education, or, if they do have access to education, it does not extend through class nine.

Even when education is accessible, it is entirely up to parents to decide whether to send their children to school or not. The government has failed to make clear to families that school is important for all of their children and to ensure that the education system accommodates all students. The government’s failure to ensure that education is compulsory violates Afghanistan’s obligations under international law and is contrary to its international development commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Afghanistan’s primary and secondary education system consists of four main types of schools. Government schools are operated and staffed by the government, often with assistance from donors, much of which flows through the Ministry of Education. Community-based education (CBE) is a model that has been used to successfully reach many Afghan girls who would otherwise be denied education; it remains entirely outside the government education system and is wholly dependent on donor funding. Madrasas, schools devoted primarily to religious instruction, teach many children but often exclude core subjects in the government’s curriculum. Private schools exist as well, providing an option for some families that can afford fees, believe they will offer a higher quality of instruction, or are in a location where there is no government school.

The war for girls’ education in Afghanistan – 16 years after the US & allies toppled the Taliban and promised to get Afghan girls back into school, why are more than half of them still out of school?

The war for girls’ education in Afghanistan – 16 years after the US & allies toppled the Taliban and promised to get Afghan girls back into school, why are more than half of them still out of school?

Barriers to Girls Education Outside of the School System

Harmful gender norms mean that, in many families, boys’ education is prioritized over girls’, or girls’ education is seen as wholly undesirable or acceptable only for a few years before puberty. In a country where a third of girls marry before age 18, child marriage forces many girls out of education. Under Afghan law, the minimum age of marriage for girls is 16, or 15 with the permission of the girl’s father or a judge. In practice, the law is rarely enforced, so even earlier marriages occur. The consequences of child marriage are deeply harmful, and they include girls dropping out or being excluded from education. Other harms from child marriage include serious health risks—including death—to girls and their babies due to early pregnancy. Girls who marry as children are also more likely to be victims of domestic violence than women who marry later.

Poverty drives many children into paid or informal labor before they are even old enough to go to school. At least a quarter of Afghan children between ages 5 and 14 work for a living or to help their families, including 27 percent of 5 to 11-year-olds. Girls are most likely to work in carpet weaving or tailoring, but a significant number also engage in street work such as begging or selling small items on the street. Many more do house work in their family’s home. Many children, including girls, are employed in jobs that can result in illness, injury, or even death due to hazardous working conditions and poor enforcement of safety and health standards. Children in Afghanistan generally work long hours for little—or sometimes no—pay. Work forces children to combine the burdens of a job with education or forces them out of school altogether. Only half of Afghanistan’s child laborers attend school.

These challenges have been compounded by a security situation that has grown steadily worse in recent years. Armed conflict is escalating, with the Taliban now controlling or contesting over 40 percent of the country’s districts. The conflict affects every aspect of the lives of civilians, particularly those living in embattled areas. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) has documented the rising impact of the war on civilians, including thousands of children who have been killed or injured.

For every child killed or injured in the conflict, there are many more deprived of education. Rising insecurity discourages families from letting their children leave home—and families usually have less tolerance for sending girls to school in insecure conditions than boys. The school that might previously have been seen as within walking distance becomes off-limits when parents fear that going there has become more dangerous.

The Taliban and other armed groups sometimes target girls’ schools, female students and their teachers for attack. Attacks on schools destroy precious school infrastructure. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch about bombings of schools, acid attacks against female students, and threats toward teachers—and a single attack can frighten hundreds of girls’ parents out of sending them for years to come. Both government security forces and Taliban fighters sometimes occupy schools, driving students away and making the school a military target.

Beyond the war, there is lawlessness, which means that on their way to school girls may also face unchecked crime and abuse including kidnapping and sexual harassment. There are increased reports of kidnapping—including of children—by criminal gangs. Like acid attacks, kidnappings have a broad impact, with a single kidnapping prompting many families in a community to keep children—especially girls—home.

Sexual harassment also presents a serious barrier to school attendance, as it is unchecked, difficult to prevent, and because of harmful gender norms can have damaging consequences for a girl’s reputation. Even when the distance to school is short, sexual harassment by boys and men along the way may force girls out of school. Families that were unsure about whether girls should study or not are easily swayed by rising insecurity into deciding it is better for girls to stay home and, often, to work instead of study.

Barriers to Girls’ Education Within the School System

A lack of schools and teachers, especially female teachers, means many girls simply do not have access to a school. Boys also face a lack of schools, but fewer schools accepting girls and greater restrictions on girls’ freedom of movement mean that girls are more deeply affected. Community-based education has allowed many girls who could not reach a school to have access to education, but without government support, this system is patchy and unsustainable.

Although government schools do not charge tuition, there are still costs for sending a child to school. Families of students at government schools are expected to provide supplies, which can include pens, pencils, notebooks, uniforms, and school bags. Many children also have to pay for at least some government textbooks. The government is responsible for supplying textbooks, but often books do not arrive on time, or there are shortages, perhaps in some cases due to theft or corruption. In these cases, children need to buy the books from a bookstore to keep up with their studies. These indirect costs are enough to keep many children from poor families out of school, especially girls, as families that can afford to send only some of their children often give preference to boys.

Overcrowding, lack of infrastructure and supplies, and weak oversight mean that children who do go to school may study in a tent with no textbook for only three hours a day. Even when schools have buildings, they are often overcrowded, with some children forced to study outside. Conditions are often poor, with buildings damaged and decrepit, and lacking furniture and supplies. Overcrowding—compounded by the demand for gender segregation—means that schools divide their days into two or three shifts, resulting in a school day too short to cover the full curriculum.

Thirty percent of Afghan government schools lack safe drinking water, and 60 percent do not have toilets. Girls who have commenced menstruation are particularly affected by poor toilet facilities. Without private gender-segregated toilets with running water, they face difficulties managing menstrual hygiene at school and are likely to stay home during menstruation, leading to gaps in their attendance that undermine academic achievement, and increase the risk of them dropping out of school entirely.

Many parents and students expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of teaching, and some students graduate with low literacy. Teachers face many challenges in delivering high quality education, including short school shifts, gaps in staffing, low salaries, and the impact that poor infrastructure, lack of supplies, and insecurity have on their own effectiveness. Teaching, which often pays under US$100 per month, is not necessarily seen as a desirable job, and people with limited education and training are often recruited as teachers. A lack of accountability can mean that teachers are frequently absent, and absent teachers may not be replaced.

There is a shortage of teachers overall, and the difficulty of getting teachers, especially female teachers, to go to rural areas has undermined efforts to expand access to school in rural areas, especially for girls. While the number of teaching positions grew annually in the years preceding 2013, it is now frozen. Seven out of 34 provinces have less than 10 percent female teachers, and in 17 provinces, less than 20 percent of the teachers are women. The shortage of female teachers has direct consequences for many girls who are kept out of school because their families will not accept their daughters being taught by a man. There is particular resistance to older girls being taught by male teachers.

Some government policies undermine the effort to get girls in school. Government schools typically have a number of documentation requirements, including government-issued identification, and official transfer letters for children moving from one school to another. While these requirements might seem routine, for families fleeing war, or surviving from one meal to the next, they can present an insurmountable obstacle that keeps children out of school. Restrictions on when children can register can drive families away, and policies excluding children who are late starting school constitute a de facto denial of education to many children. These barriers can be particularly harmful for girls, as discriminatory gender roles may mean that girls are more likely to lack identification, and to seek to enroll late and thus be affected by age restrictions and restrictions on enrolling mid-year. When families face difficulty obtaining the documentation necessary for a child to register or transfer, they may be less likely to go to great efforts to secure these documents for girls.

Afghanistan has well over a million internally displaced people, with more people being displaced all the time. Internally displaced families often face insurmountable barriers in obtaining the documentation they need to get their children into school in their new location. Families returning from other countries—often because of deportation—face similar challenges.

Community-based education programs (CBEs) are often an Afghan girl’s only chance at education. The opening of a nearby CBE can mean access to education for girls who would otherwise miss school, and research has demonstrated the effectiveness of CBEs at increasing enrollment and test scores, especially for girls. CBEs can be an effective strategy to tackle many of the systemic barriers to girls’ education, including the long distances to school, insecurity on the route to school, and the lack of female teachers, among others. However, to date CBEs are exclusively operated by NGOs and entirely funded by foreign donors. The absence of long-term strategic thinking by government and donors exposes CBE programs—and students—to unpredictable closures, which can compromise students’ educational future.

As Afghanistan’s school system struggles—and often fails—to meet the needs of students, there is very little extra support or access to education for children who have disabilities.

Regular government schools typically have no institutionalized capacity to provide inclusive education or assist children with disabilities. Children with disabilities who attend regular schools are unlikely to receive any special assistance. Only a few specialized schools for children with disabilities exist, and they are of limited scope. With no system to identify, assess, and meet the particular needs of children with disabilities, they often instead are kept home or simply fall out of education.

The corruption present in most Afghan institutions undermines the education sector as well, most markedly in the large bribes demanded of people seeking to become teachers. Afghanistan is ranked as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, and Afghans asked to name the three most corrupt institutions in Afghanistan listed the Ministry of Education third, out of 13 institutions. Corruption takes many forms in the education sector, including: corruption in the contracting and delivery of construction and renovation contracts; theft of supplies and equipment; theft of salaries; demand for bribes in return for teaching and other positions; demands for bribes in return for grades, registration of students, provision of documents, among other things; and “ghost school” and “ghost teachers”—schools and teachers that are funded but do not actually exist.

Donor Support to Education in Afghanistan

While Afghanistan has in recent years been one of the largest recipients in the world of donor funding, only between 2 and 6 percent of overseas development assistance has gone to the education sector. Bureaucratic hurdles, low capacity, corruption, and insecurity have contributed to even these funds often going unspent by the Afghan government. The government spends less on education than certain international standards recommend, as measured against gross domestic product (GDP) and the total national budget, reflecting in part how donors have allocated their funding.

In November 2016, donors and the Afghan government convened for the Brussels Conference on Afghanistan, where donors pledged US$15.2 billion in aid for Afghanistan over the next four years. The goal of the conference organizers was to sustain aid at or near current levels, and this figure was seen as representing an achievement of that goal.

Despite the large pledges made at the Brussels Conference, the overall outlook for aid in Afghanistan is downward. NGOs report that they are feeling the effects of reductions in funding, and this is already having an impact on the many girls studying outside the government’s education system. The impact on girls’ education could be even greater in the future, as government fixed costs—especially for security forces—take up a growing proportion of a declining aid budget.

Another change in donor funding that has affected girls occurred as international troops withdrew from many provinces in 2014, taking their funding with them. Under the system previously in place through the NATO military command, specific troop-contributing countries had security responsibility for each province, through a system of Provincial Reconstruction Teams. These countries typically invested in development aid, including for education, in the same province. As the troops drew down, the aid funding typically did as well. The result was that some provinces, particularly those that had been recipients of higher levels of aid funding, have already seen a steep decline in funds.

Legal Obligations

Education is a basic right enshrined in various international treaties ratified by Afghanistan, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Afghanistan has also ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which includes an obligation to ensure women equal rights with men, including in the field of education.

Under international human rights law, everyone has a right to free, compulsory, primary education, free from discrimination. International law also provides that secondary education shall be generally available and accessible to all.

Governments should guarantee equality in access to education as well as education free from discrimination. The Afghan government has a positive obligation to remedy abuses that emanate from social and cultural practices. Human rights law also calls upon governments to address the legal and social subordination women and girls face in their families, provisions violated by Afghanistan’s tolerance of a disproportionate number of girls being excluded from school.

International law obligates governments to protect children from child marriage, and from performing work that is hazardous, interferes with a child’s education, or is harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral, or social development. Children with disabilities have a right to access to inclusive education, and to be able to access education on an equal basis with others in their communities.

In implementing their obligations on education, governments should be guided by four essential criteria: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptability. Education should be available throughout the country, including by guaranteeing adequate and quality school infrastructure, and accessible to everyone on an equal basis. Moreover, the form and substance of education should be of acceptable quality and meet minimum educational standards, and the education provided should adapt to the needs of students with diverse social and cultural settings.

Governments should ensure functioning educational institutions and programs are available in sufficient quantity within their jurisdiction. Functioning education institutions should include buildings, sanitation facilities for both sexes, safe drinking water, trained teachers receiving domestically competitive salaries, teaching materials, and, where possible, facilities such as a library, computer facilities and information technology. It is widely understood that any meaningful effort to realize the right to education should make the quality of such education a core priority.

The Afghan government also has a legal obligation to take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures to protect children from all forms of physical and mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, and ma”ltr”eatment. Permitting the use of corporal punishment is inconsistent with this obligation.

In the past 16 years, the Afghan government and its international backers have made significant progress in getting girls into school. But serious obstacles are still keeping large numbers of girls out of school and there is a real risk that recent gains will be reversed.

It is therefore urgent that the Afghan government and international donors redouble their efforts to remove or mitigate the barriers to girls’ education enumerated in this report in order to guarantee girls’ right to primary and secondary education in Afghanistan.