Human Wrongs Watch – Bullet holes, bloodstains and brain matter marked the walls of an empty barn, a crime scene processed to document the worst crime in Europe since the Second World War: the deliberate killings of more than 7,000 men and boys from the Bosnian town of Srebrenica. Journalists and human rights researchers had pieced together the horrifying story based on eyewitness accounts from the few who survived; and then investigators from the Yugoslav war crimes tribunal built a genocide case by collecting evidence from killing sites and exhuming mass graves.

At the time war erupted amidst the breakup of socialist Yugoslavia in 1991, human rights investigations in Europe largely focused on the rights of political dissidents and minorities within the former Soviet bloc. But with the conflict raging through Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia, human rights activists helped put war crimes firmly on the international agenda – with help from journalists who often didn’t understand the legal implications of the horrors they reported on every day.

A boy going for water rushes across a dangerous intersection where some 20 people had, in recent weeks, been killed by snipers. Mostar was under siege and its residents were desperate for water. EXPAND

A boy going for water rushes across a dangerous intersection where some 20 people had, in recent weeks, been killed by snipers. Mostar was under siege and its residents were desperate for water. EXPAND

A boy going for water rushes across a dangerous intersection where some 20 people had, in recent weeks, been killed by snipers. Mostar was under siege and its residents were desperate for water. September 7, 1993. © 1993 Corinne Dufka

Yugoslavia’s bloody breakup was most brutal in the republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, home to an ethnic patchwork of Bosnian Muslims, Serbs, Croats and others. Ethnically homogenous Slovenia broke away with minimal casualties, and Croatia, where Serb and Croat communities were generally well-defined , divided along ethnic lines, albeit with bloody conflict in areas with mixed populations. But Bosnia could not be surgically split nor easily absorbed into an expanded “Greater Serbia” or “Greater Croatia.”

Under orders from Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, a career communist turned nationalist demagogue, Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb forces besieged and systematically bombarded civilians, razed Muslim areas, expelled entire communities, burned down or blew up houses and mosques, and raped women and girls as a tactic of war. During three years of fighting, Bosnian Croat forces and in some cases Bosnian Muslim forces also committed atrocities against civilians.

Reporters on the ground struggled at first to comprehend what was to become known as “ethnic cleansing.” That first summer, one group racing to cover the siege of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, drove through burning villages in eastern Bosnia, negotiating checkpoints guarded by armed men without truly grasping what lay in store. They were so focused on reaching the big story in Sarajevo that they missed the start of the campaign to brutally drive Bosnian Muslims from their homes and communities.

Four months after the fighting started in Sarajevo on April 6, 1992, Human Rights Watch published “War Crimes in Bosnia-Herzegovina,” its first report on violations of the laws of war and a horrifying, meticulously researched call for action, for accountability, for a threat of justice tomorrow that might give commanders of today pause for thought.

It was a pioneering attempt to marry real-time field reporting of war crimes with lobbying for an international tribunal to punish military and political leaders responsible for atrocities so severe, said Human Rights Watch, that they “raise the question of whether genocide is taking place.”

Lotte Leicht, now our European Union director, spent months investigating crimes in a new way on behalf of a coalition of lawyers. “We were trying to prove that you could go to an active war zone and uncover facts with such rigor that no one could seriously contest them. And it turned out we were right.”

On May 25, 1993, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 827, formally establishing the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). This was a step by Western powers that proved to be momentous without the airstrikes many of us thought would be needed to end the war (and the war crimes). Inspired by this, as associate counsel for Human Rights Watch, Richard Dicker, lobbied governments around the world, starting with The Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand, Argentina, and South Africa, to set up a permanent international court able to investigate and prosecute crimes committed anywhere in the world, not just the former Yugoslavia.

“Once the Yugoslav tribunal got up and running, we started sending them our material. We were doing all we could to see that the facts we uncovered made it into the hands of prosecutors with a mandate to launch criminal investigations. Our reports helped lead them to evidence,” said Dicker, who went on to set up the international justice program at Human Rights Watch and helped to draft the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Some 300 Muslim residents of Mostar taken prisoner by Bosnian Croat forces are led down a dirt road towards an abandoned factory. This new wave of ethnic cleansing being arried by Croats was accompanied by heavy fighting in Mostar, May 11, 1993. © 1993 Corinne Dufka

The ICTY got up and running in 1993, but global attention did not focus on the court until the trial of Slobodan Milosevic began in 2002. In a moment of high courtroom drama that year, Human Rights Watch’s Fred Abrahams recounted our sharing our findings with Milosevic’s office in Belgrade while Milosevic cross-examined him.: “Yes, Mr Milosevic, we mailed our reports to you so that you would know exactly what was happening at the hands of Serbian forces.” Under international humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war, Milosevic was responsible for atrocities committed by his troops if he knew or should have known about the crimes but did nothing to stop or punish them, and Human Rights Watch wanted to ensure he couldn’t plausibly claim ignorance.

Sarajevo under siege housed tens of thousands of displaced people, trapped without water, electricity or heating during grim Sarajevo winters, dependent on food packages from aid agencies, threatened by shells and snipers. When the explosions started, civilians would rush to neighboring apartments that faced away from danger. Snipers nested in apartment buildings close to the invisible front line separating the armies, picking off men, women, children, the elderly and sowing terror. For more than three years, photos and video from news crews showed people sprinting across city intersections, across tramlines, dodging through rubble and hiding around corners. The world watched the slaughter on TV, with the lightly armed UN Protection Force powerless to keep Sarajevans safe.

Mortar and artillery shells crashed into apartment blocks, schools, banks, markets, and hospitals, destroying thousands of lives. One victim, 9-year-old Sidbela Zimic, was killed when a Serb shell hit their small playground. She died in her mother’s arms just outside her home. Minela, her 11-year-old sister, had just gone inside for an English lesson and survived. Three other girls were killed. “We played to forget about the war,” Inesa Olovcic, 11, told me at the time.

For many journalists, Bosnia was a transformative experience; many of us felt deeply frustrated to keep reporting without seeing any change. It’s no coincidence that so many reporters and photojournalists I knew there – Corinne Dufka, Laura Pitter, Pierre Bairin and Stacy Sullivan – ended up working for Human Rights Watch.

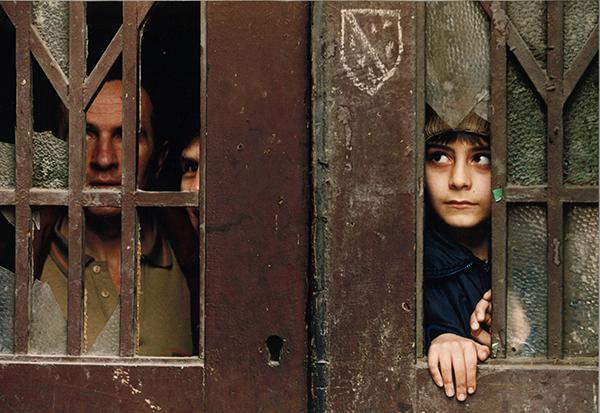

A family peer out their front door which was damaged a few days earlier when a huge mortar bomb which killed at least 68 people crashed into a busy Sarajevo market. February 9, 1994. © 1994 Corinne Dufka

A family peer out their front door which was damaged a few days earlier when a huge mortar bomb which killed at least 68 people crashed into a busy Sarajevo market. February 9, 1994. © 1994 Corinne Dufka

Roy Gutman of Newsday famously broke the story of the Serb concentration camps in Omarska and Keraterm after interviewing survivors. In denying Gutman’s account, the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic invited British reporters to visit. They did – and filmed prisoners so emaciated they recalled images from Nazi death camps. Gutman went on to edit “Crimes of War – What the Public Should Know,” to help journalists better understand the legal side of conflict.

A guard at Omarska, Dusan Tadic, was the first person tried by the ICTY – and indeed, the first person since the Nuremberg Trials after World War II to face an international war crimes court. In 1997 he was acquitted of murder but convicted of beatings and persecution, sentenced to 20 years in prison and released early in 2008.

In its first year, the tribunal indicted only lower-level commanders. Then, in the summer of 1995, came Srebrenica. Despite three years of atrocities, it was still hard to believe the fragmented stories filtering out in the days after Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladic’s troops pushed out the few Dutch peacekeepers guarding the UN “safe area” of Srebrenica, where more than 20,000 Bosnian Muslims lived under siege. Women and children had mostly been bused across the front line to relative safety in Tuzla – but more than 8,000 men and boys were missing. Family members didn’t know if they were alive or dead.

Human Rights Watch hired Laura Pitter, then a reporter, to help investigate what happened and write a report. “We knew the men and boys had disappeared but we didn’t know what happened to them.,” said Pitter, now senior national security counsel at Human Rights Watch. “Then we found the witnesses. Some had seen executions, others dead men by the side of the road. Others had actually survived massacres by hiding under dead bodies for days, then crawling out from under them and walking through the woods to Tuzla.”

Srebrenica galvanized global action against the Serbian leadership. NATO airstrikes along with a major Croatian military offensive helped push Milosevic to the negotiating table to sign the Dayton peace accords in November 1995. Within weeks, the court charged Karadzic and Mladic with genocide and crimes against humanity for their ethnic cleansing of Bosnia and their use of snipers to target civilians in besieged Sarajevo. They soon added Srebrenica to the list and the two were excluded from the Dayton peace talks in late 1995.

With NATO troops deployed to police this new peace, reporters and human rights investigators were suddenly able to work in Serb-controlled areas. Over the verdant, wooded hills around Srebrenica we saw the bodies of those who had been desperately trying to flee, unarmed and gunned down by Serb forces. We visited a school where people were held, then trucked to an empty field dug up by bulldozers, lined up and shot. We walked around mass graves that would soon be examined for evidence, the bodies exhumed so that grieving relatives would at least know what happened. They might also hope for justice.

Lacking a police force, the ICTY needed help to secure arrests. But as the peace took hold, NATO’s political bosses didn’t seem interested in having their troops apprehend Bosnia’s most wanted. Karadzic moved fairly freely for the first few years, always accompanied by bodyguards, while Mladic was rumored to live under a mountain at military headquarters, and/or to tend a flock of goats named after UN commanders and Western politicians. As a UN spokesman said in 1997, their continued freedom was “an insult to the memory of the victims and an embarrassment to the international community.”

That’s why Human Rights Watch and other groups set up the Arrest Now campaign in 1997: to put pressure on NATO peacekeepers to arrest war crimes suspects in Bosnia. When NATO claimed their peacekeepers would arrest the suspects if they could only find them, Human Rights Watch’s Benjamin Ward created a widely reproduced map showing the location of NATO bases and known whereabouts of the suspects, giving the lie to the idea that they could not be found. After lengthy advocacy meetings with NATO governments and at headquarters, we began to see real progress, including arrests by NATO countries previously reluctant to act.

Human Rights Watch kept digging up the dirt, with forensic analyses of past crimes in several towns, including Foca, a town in southwestern Bosnia infamous for the virulence of its purges of Muslims. One victim was Emina Cerimovic, forced to flee with her family when she was 8. The war took many things from her, including her father. She endured more than two years of war until her remaining family escaped to Sweden, where she lived as a refugee.

Foca was the focus of another ICTY case, a landmark prosecution of sexual enslavement and rape as crimes against humanity. Three Bosnian Serb army officers were sentenced for organizing and running rape camps in Foca, where soldiers had free access to the women and girls, some as young as 12. It was also the first war crimes court to prosecute sexual violence against men and boys.

Despite – perhaps because of – her experience, Cerimovic went to law school, where she learned of Human Rights Watch’s work during the war in Bosnia. “Ever since, I’ve looked up to Human Rights Watch and dreamed of doing what Human Rights Watch investigators did back then,” she said. Cerimovic spent a summer helping to exhume mass graves in eastern Bosnia, then worked on national war crimes trials before joining Human Rights Watch. She now works to expose and ease the plight of 21st-century refugees in Europe, particularly those with disabilities.

But in 1998, by the time Human Rights Watch published the Foca report, a new Yugoslav fire was burning: Kosovo.

The Serbian province of Kosovo, populated mostly by ethnic Albanians, held an almost sacred position as the site of an historic battle on June 28, 1389 between Orthodox Christian Serbs and the Muslim Ottoman Empire. Six hundred years later, in 1989, Milosevic used Kosovo as a rallying cry and springboard for his political ascent. By the spring of 1998, the separatist Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) was at war with the Serbian government.

Human Rights Watch had been reporting on human rights abuses in Kosovo since 1992 and ramped up reporting as fighting broke out. The first report focused on several massacres by Serbian forces, as well as violations by the KLA. The second documented the murder of 21 members of the Delijaj family in September 1998, based on interviews with witnesses and surviving relatives. Two were still missing in mid-October and I watched as local residents hauled the body of Hajriz Delilaj from a nearby well.

After failed negotiations, Western governments decided to take military action and NATO began another bombing campaign (which also caused about 500 civilian deaths). In response, Serbian forces rampaged through Albanian villages in Kosovo, forcibly expelling about 850,000 people. They crossed the borders to Albania and Macedonia, with stories of massacres, rapes, and torture.

I had gone to the Albanian border town of Kukes, overwhelmed by the tide of misery, to report on the endless horror stories. Among the aid tents I found Abrahams, who was there for Human Rights Watch, collecting first-hand accounts. He wrote “A Village Destroyed,” which detailed what happened in one village in May 1999, and used photographs taken by the attackers and found nearby to identify those responsible. Years later, Serbian authorities arrested some of these men and they are currently standing trial for war crimes in Belgrade.

As Cuska was ravaged, Milosevic, creator of the bloodstained strategy to create a “Greater Serbia,” was finally indicted by the ICTY and charged with 66 counts of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes. Although he was a sitting head of state, Serbian authorities arrested and detained him in Belgrade. And on June 28, Serbia’s most significant national day, he was surrendered to The Hague.

“That moment changed history,” Dicker said. “That’s real progress: that a president can be brought to a court room and fairly held to account for such serious crimes.”

“Under Orders,” Human Rights Watch’s definitive book on Kosovo war crimes, written by Abrahams and Ward, was used as evidence at the trial.

Milosevic pleaded not guilty and, living up to his reputation for arrogance, insisted on representing himself. Abrahams testified in the trial, talking about the murdered Delijaj family and other crimes. But in 2006 Milosevic died unexpectedly, without a verdict, robbing his victims of genuine justice. It was a low moment, a dispiriting end to the “trial of the century.”

There was better news in the summer of 2008, when Karadzic, on the run for 12 years yet able to carry out an alternative medicine practice, was arrested in Belgrade by Serbian security forces – just as European foreign ministers were meeting to discuss European Union ties to Serbia. He was detained in Milosevic’s old cell and charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. In 2016, the ICTY convicted him on 10 of 11 counts, including the Srebrenica genocide and for the siege of Sarajevo, and sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Cerimovic, Pitter and I celebrated the verdict, but for Cerimovic it was a bittersweet moment. “It was disappointing that he was only convicted for crimes against humanity in my home town,” she said. “I wish he had been found guilty of genocide in Foca as well – that would give us the dignity and justice we deserve and hope that maybe we would get an apology.” Foca, she points out, is still ethnically “cleansed”; Bosnian Muslims made up more than 42 percent of the pre-war population but only 7 percent in 2013.

Over its 25 years, the ICTY Processed 151 defendants, including 95 Serbs, 29 Croats and 9 Bosnian Muslims, as well as a handful of Kosovo Albanians, Montenegrins and Macedonians, and a few of unknown ethnicity. One defendant was a woman: Bosnian Serb prime minister Biljana Plavsic. Naser Oric, the Bosnian Muslim commander in Srebrenica, revered for keeping the enclave alive for almost four years, was convicted and acquitted on appeal; the Bosnian chief of staff, Rasim Delic, died while appealing his three-year sentence. One of the most senior Bosnian Croat generals, Jadranko Prlic, was sentenced to 25 years. In an example of the court’s wide reach, the Croatian general Ante Gotovina was arrested in the Spanish Canary Islands on an international warrant.

A family flee on foot through heavy snowfall after fleeing fighting in their town, November 14, 1993. © 1993 Corinne Dufka

Still at large 16 years after being indicted was the so-called Butcher of Bosnia: Ratko Mladic, but his time too was running out. In May 2011, he was arrested by special police forces in Serbia and transferred to The Hague. Unlike Karadzic, his partner in mass atrocities, Mladic had a lawyer but he too was convicted. In late 2017 the ICTY convicted him of genocide and crimes against humanity for Srebrenica and Sarajevo, and sentenced him to life in prison.

So the tribunal moved through its remaining appeals, upholding convictions on November 29 for the last six defendants, Bosnian Croat generals convicted for war crimes. In a bizarre final chapter, Slobodan Praljak greeted the appellate ruling by drinking cyanide and dying in the dock and in doing so, inadvertently drew more attention to the Croatian government’s own ethnic cleansing campaign in Bosnia. The court will formally close on December 21.

Twenty-four years ago, the idea that a court without a police force could bring to the dock those responsible for the most serious war crimes seemed quixotic at best. But years of dogged investigation and relentless advocacy, including convincing the European Union to condition closer ties for Croatia and Serbia on their cooperation, yielded extraordinary results: 161 people indicted, major and undoubtedly lasting developments in international criminal law, and a judicial record of what happened after the breakup of the former Yugoslavia.

“It took years but the Yugoslav court brought down the untouchables,” Dicker said. “It marginalized the bad actors who likely would have wreaked even more havoc. The process was imperfect, slower than we would have liked and the tribunal made mistakes along the way. But it showed that justice is possible when there is political will. And that’s the legacy we should take forward.”