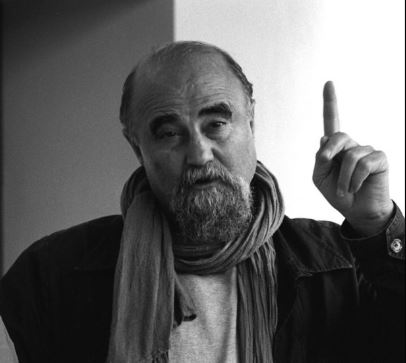

Abbas Attar, an Iranian-born photographer who documented cataclysmic events throughout the world, including the Iranian revolution, and developed a particular interest in the role of religion in them, died on Wednesday in Paris. He was 74.

His agency, Magnum Photos, announced his death. It did not give a cause.

Abbas, as he referred to himself professionally, was known for dramatic black-and-white photographs delivered with a point of view, especially in his book “Iran Diary 1971-2002” (2002), a collection of images and text presented as a sort of journal. When the events that resulted in the overthrow of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi in 1979 began, Abbas supported change, but he soon became disillusioned with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who took over the government.

“When the revolution started, it was democratic,” The Toronto Star quoted him as saying in 2013. “It was my country, my people and my revolution. Then, slowly, it was being hijacked.”

A turning point, he said, was the execution of four generals after a secret trial. He photographed their corpses in a morgue.

“Something that we learned,” he said, “is that the extremists always win. That was my main lesson from the revolution. The extremists were prepared to kill, imprison, torture — everything. So they won.”

Abbas was born in 1944 in a part of Iran near the Pakistan border. (Little biographical information about him was available.) When he was a boy his family relocated to Algeria; he said that growing up during that country’s war of independence sparked his interest in documenting political events.

He taught himself to use a camera, and among his earliest jobs was working for the International Olympic Committee at the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico. He would return to Mexico in the mid-1980s, taking pictures throughout the country over three years and producing the 1992 book “Return to Mexico: Journeys Beyond the Mask.”

In the 1970s he worked for the French agencies Sipa and Gamma. Early in that decade he was in Africa, covering the aftermath of the Biafran war in Nigeria and other events. He then found himself back in Iran.

“My family is from Iran,” he told Vice in 2015, “but it isn’t as if I felt particularly Iranian back then. But I did feel that things had to change — you can’t just have some shah making all the important decisions for an entire country.”

As the situation became more unstable and it became clear to him that the revolutionaries were no better than the regime they were replacing, he faced pressures from friends.

“They urged me not to show the revolution’s negative side to the world,” he said. “The violence was supposed to come from the shah, not the protesters. I told them that it was my revolution as well, but I still needed to honor my duty as a journalist — or a historian, if you will.”

He left the country in 1980 and did not return for 17 years. The revolution, though, had instilled in him an interest in what people throughout the world were doing in the name of God.

“It was obvious after two years that the wave of Islamism was not going to stop at the borders of Iran,” he said in a video interview with The British Journal of Photography in 2009. “It was going much beyond the borders.”

He began by examining that phenomenon, resulting in the book “Allah O Akbar: A Journey Through Militant Islam” (1994), which recounted his travels through 29 Islamic countries.

“When you’ve started with God you might as well stay with him,” he said, explaining why he went on to look at Christianity, paganism, Buddhism and more. It was an examination not of personal faith, he said, but of how faith can be deployed and twisted in other spheres.

“What I’m interested in is the political, social, economic, even psychological aspects of religion,” he said, adding, “More and more, nations are defining their identities referring to religion.”

Information on survivors was not immediately available.

If his work often put him in the middle of trouble spots, Abbas was not necessarily interested in images of blood and weaponry.

“Most photographers, when they say they’re war photographers, they’re not really war photographers; they’re battle photographers,” he said in the video interview. “War does not limit itself to boom-boom, to the battle itself. Wars are very, very complex phenomenons, because they have a source, and it takes a while to come up, then it happens, and there are consequences. I’m more interested in the why and the afterwards of the wars.”

He played down the part of his work that involved putting himself in harm’s way.

“They say ‘courage’ — O.K., you have to be courageous,” he said. “But for me courage is a lack of imagination. You cannot imagine that it’s going to happen to you, therefore you go to the battle.”