A woman picks cotton during the 2015 cotton harvest, which runs from early September to late October or early November annually. © 2015 Simon Buxton/Anti-Slavery International

“Cotton is mandatory for everyone. The government gave the orders [to pick] and you will not go against those orders…. If I refuse, they will fire me…. We would lose the bread we eat.”

−Uzbek schoolteacher, October 2015, Turtkul, Karakalpakstan

For several weeks in the fall of 2015, government officials forced Firuza, a 47-year-old grandmother, to harvest cotton in Turtkul, a district in Uzbekistan’s most western region, the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan. The local neighborhood council, the mahalla committee, had threatened to withhold child welfare benefits for her grandson if she did not go to the fields to harvest cotton. These same officials forced another woman, Gulnora, to harvest cotton for the same length of time. Although Gulnora worked, the government refused to pay her child welfare benefits, promising to consider reinstating them if she worked in the fields the next spring. The Uzbek government forces enormous numbers of people to harvest cotton every year through this kind of coercion.

The government’s abusive practices are not confined to adults. During the 2016 harvest the government forced young children to work in the cotton fields. In Ellikkala, a district neighboring Turtkul, officials from at least two schools ordered 13 and 14-year-old children to pick cotton after school. The Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights saw children working in one of the cotton fields, and a teacher ordering the children to hide. The World Bank has funded an irrigation project in these districts on the condition that the Uzbek government comply with laws prohibiting forced and child labor. Despite this agreement, the Uzbek government has continued to force people, including children, to work within the project area.

Withholding child benefits and other welfare payments is just one of the penalties the government has used to force people to work. The government has threatened to fire people, especially public sector employees who are among the lowest paid in the country. Students who refused to work faced the threat of expulsion, academic penalties, and other consequences. People living in poverty are particularly susceptible to forced labor, as they are unable to risk losing their jobs or welfare benefits by refusing to work and cannot afford to pay people to work in their place.

Based on interviews with victims of forced labor in September to November 2015, April to June and September to November 2016, and early 2017, leaked government documents, and statements by government officials, this report details how the Uzbek government forced students, teachers, medical workers, other government employees, and private-sector employees to harvest cotton in 2015 and 2016, as well as prepare the cotton fields in the spring of 2016. The report documents forced adult and child labor in one World Bank project area and demonstrates that it is highly likely that the Bank’s other agriculture projects in Uzbekistan are linked to ongoing forced labor in light of the systemic nature of the abuses. The report also finds that there is a significant risk of child labor in other Bank agricultural projects in the country.

Uzbekistan is the fifth largest cotton producer in the world. It exports about 60 percent of its raw cotton to China, Bangladesh, Turkey, and Iran. Uzbekistan’s cotton industry generates over US$1 billion in revenue, or about a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), from one million tons of cotton fiber annually. These funds go into an opaque extra-budgetary account, the Selkhozfond, housed in the Ministry of Finance, that escapes public scrutiny and is controlled by high-level officials.

Campaigns by a number of groups against forced and child labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton sector have resulted in boycotts of Uzbek cotton. For example, 274 c0mpanies have pledged not to knowingly source cotton from Uzbekistan because of forced and child labor in the sector. Despite this, the World Bank remains active in the country’s agriculture sector providing a total of $518.75 million in loans to the government for projects in this sector in 2015 and 2016.

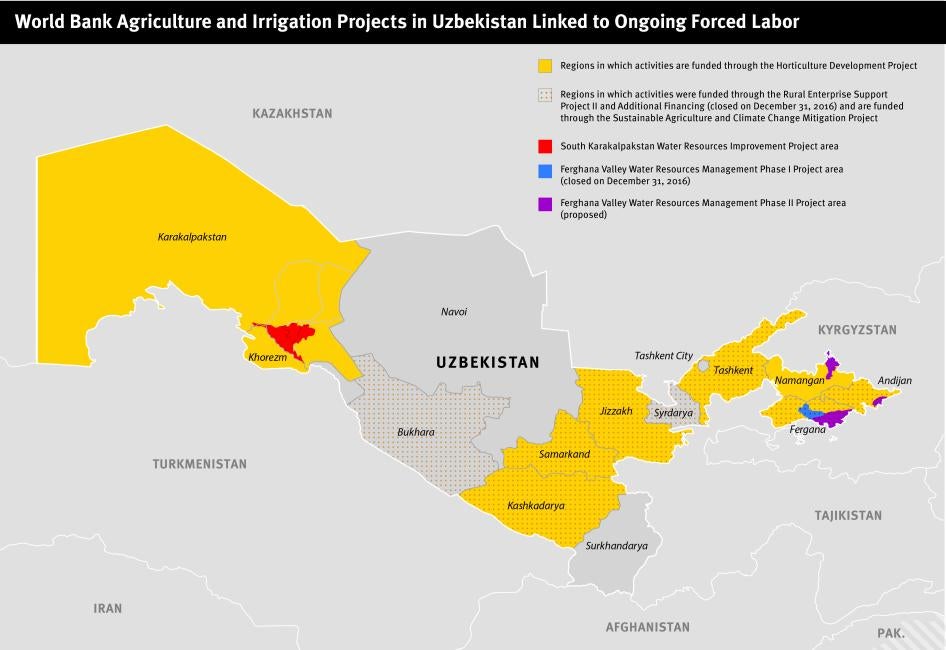

In Turtkul, Beruni, and Ellikkala districts in Karakalpakstan, the World Bank has worked with the Uzbek government since April 2015 under a $337.43 million irrigation project. Cotton is grown on more than 50 percent of the arable land within this project area. The World Bank secured a commitment from the Uzbek government to comply with national and international forced and child labor laws in the project area and agreed that the loan could be suspended if there was credible evidence of violations.

Since the World Bank approved this project in 2014, the Uzbek government has continued to force people, sometimes children, to work in the cotton sector in Turtkul, Beruni, and Ellikkala, including within the Bank’s project area. Independent groups, including the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights, submitted evidence of forced and child labor to the World Bank during and following the 2015 harvest, which runs from early September until early to mid-November annually. Instead of suspending its loan to the government, in line with the 2014 agreement between the two parties, the World Bank increased its investments in Uzbekistan’s agriculture industry through its private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Shortly after the 2015 cotton harvest, the IFC invested in a government joint venture with a subsidiary of Indonesia’s Indorama Corporation, Indorama Kokand Textile, a leading cotton yarn producer in Uzbekistan. In December 2015 the IFC agreed to loan Indorama $40 million to expand its textile plant, which uses solely Uzbek cotton. Given the scale of forced labor in Uzbekistan and its systemic nature, it is highly unlikely that a company could source any significant quantity of cotton from Uzbekistan at present that has not been harvested, at least in part, by forced laborers. There is also a significant risk of child labor.

According to the IFC, Indorama tracks its purchases from sites where cotton is processed to mitigate the risk of child and forced labor. Together with the IFC, Indorama has developed a system for rating the risk level of districts in which gins are located. But this system is deeply inadequate. The IFC’s Environmental and Social Performance Standards, which are designed to prevent the IFC from investing in projects that harm people or the environment, require clients to identify risks of, monitor for, and remedy forced and child labor in their supply chains. The Performance Standards provide that where remedy is not possible, clients must shift the project’s primary supply chain over time to suppliers that can demonstrate that they do not employ forced and child labor.

The World Bank is also heavily invested in the country’s education sector, where forced and child labor have undermined access to education, and its quality, because teachers, and students, including children, have had to leave school for up to several months to work in cotton fields. Through direct funding and the Global Partnership for Education, a multistakeholder funding platform, the World Bank provides almost $100 million in financing for education projects in Uzbekistan.

The government has greatly reduced the number of children it forces to work since 2013, primarily by ordering government officials down the line of command to mobilize adults rather than children. However, Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum documented more cases of state-organized child labor through schools mobilizing children in 2016 than in the previous year. For example, in addition to child labor in Karakalpakstan described above, in 2016 children and teachers in two districts in Kashkadarya and a school employee in rural Fergana told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that local officials required schools to mobilize children as young as 10 or 11 years old to pick cotton and suspended classes during this period. They noted that in several districts this was worse than 2015, when children received some classes prior to being sent to pick cotton.

The World Bank’s Unsuccessful “Mitigation” of Forced Labor

The World Bank has a long history of investing in Uzbekistan’s agriculture sector, but a poor record of addressing forced and child labor in the projects it funds. The Bank only acknowledged this problem after forced laborers filed a complaint with the World Bank’s independent accountability mechanism, the Inspection Panel, in 2013.Thatcomplaint alleged that a Bank agriculture project was contributing to the perpetuation of forced and child labor in Uzbekistan.

In response, the World Bank introduced several measures to mitigate the risk of these labor abuses being linked to existing and proposed Bank projects. It required the government to comply with national and international laws on forced and child labor. It also committed to establish thirdparty monitoring of labor practices in the Bank’s project areas and to implement a grievance mechanism through which victims of forced labor would be able to complain and receive some redress. These mitigation measures do not adequately address government-organized, systematic forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton sector. Ultimately, the Bank found that it could not implement some of its commitments, so it settled for weaker measures.

For example, the World Bank contracted the International Labour Organization (ILO), a tripartite UN agency made up of governments, employer organizations, and worker representatives, to monitor forced and child labor in partnership with the Uzbek government, instead of independently monitoring the government’s practices. The ILO has an important role to play in promoting fundamental labor rights in Uzbekistan. However, itallowed the involvement of government and government-aligned organizations in the monitoring effort. The lack of independence of labor unions in Uzbekistan further compromises the ILO’s work in Uzbekistan. Under this structure, in reality, the government that mandates forced labor and utilizes child labor is allowed to monitor itself. While the World Bank has acknowledged these limitations privately, publicly it continues to refer to the ILO as undertaking “independent monitoring.”

The credibility of the ILO’s findings has been further undermined by evidence that the government coached ILO interviewees. The ILO reported that “Many interviewees appeared to have been briefed in advance.” Numerous people told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that government officials or their supervisors told people to say they were local and unemployed, picking cotton voluntarily, or that they worked as cleaners or guards in their schools and hospitals instead of teachers and medical staff. If the monitors already knew that they were teachers, then they were to say that they voluntarily picked cotton after they had finished teaching classes.

There is no proper grievance mechanism either. Instead of an independent mechanism, the Ministry of Labor and a government-controlled trade union federation are responsible for obtaining feedback from workers, undermining its credibility among workers. This system has resulted in reprisals against complainants and a general dismissal of their concerns, both of which have compounded the lack of trust in the mechanism.

The World Bank has not recognized that Uzbekistan has breached its loan agreements with the Bank in continuing to force adults and some children to work in its project area, despite receiving evidence from independent groups including Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum of these abuses. The ILO similarly reported to the World Bank that it observed indicators of forced labor in the country in 2015 and that there were ongoing risks of forced labor in 2016 including in Bank project areas.

Instead of suspending key loans to Uzbekistan, the World Bank has lauded the government for its efforts, saying, “The government is taking actions, albeit in a very incremental and cautious manner, that reflect a genuine commitment to abide by its national laws and international commitments.” Bank staff have pointed to legal changes, the government’s cooperation with the ILO, increased training on forced and child labor, the promise of mechanization, the government’s commitment to reduce the land on which it requires farmers to grow cotton, and reports that at least one government official was dismissed for violating forced and/or child labor laws in November 2016. The Bank also noted that, according to the ILO, the number of people that refused to work in the cotton harvest doubled from 2014 to 2015. While these are notable developments, none of these steps directly addressed the fact that forced and child labor continue to be linked to Bank-supported projects in violation of the Bank’s agreements with the Uzbek government.

Threats and Reprisals Against Human Rights Defenders

The Uzbek-German Forum’s monitors, as well as other people conducting human rights and labor rights monitoring work, faced constant risk of harassment and persecution in 2015 and 2016. In several regions, local authorities, including police, prosecutors, and representatives of mahalla committees, called in monitors for questioning, accused them of being involved in illegal or “bad” activities, threatened them with charges, loss of jobs, or other penalties, and in some cases confiscated their research materials. Local police and central government officials have also arbitrarily prevented monitors from traveling in connection with their human rights work.

In 2015 this harassment reached unprecedented levels as the government used arbitrary arrest, threats, degrading ill-treatment, and other repressive means to undermine the ability of monitors to conduct research and provide information to the ILO and other international institutions. One monitor, Dmitry Tikhonov, had to flee the country and another, Uktam Pardaev, was imprisoned for two months and released on a suspended sentence. Police told Pardaev that he is subject to travel restrictions and a curfew, although these are not stipulated in the sentence, and have surveilled and intimidated his relatives and friends. He risks going to prison if found to violate conditions of release, which he believes could be used to retaliate against him for speaking out about human rights abuses.

In 2016 only one Uzbek-German Forum monitor, Elena Urlaeva, continued to work openly, and she was subjected to surveillance, harassment, arbitrary detentions and other abuses. On March 1, 2017, police again detained Urlaeva. After reportedly insulting and assaulting her, police sent Urlaeva to a psychiatric hospital for forced treatment. The hospital released her on March 23. Urlaeva said she believes authorities detained her to prevent her from meeting with representatives of the World Bank and the ILO. In Karakalpakstan, where the World Bank irrigation project is being implemented, authorities questioned and intimidated another Uzbek-German Forum monitor, who did not work openly, and amember of his family, suspecting him of monitoring. Security forces also arrested an independent monitor in this area and briefly detained him.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has raised concerns about forced labor and the treatment of individuals attempting to monitor labor practices in Uzbekistan. Human Rights Watch and others have repeatedly recommended that the Bank include a covenant in loan and financing agreements explicitly allowing independent civil society and journalists unfettered access to monitor forced and child labor, along with other human rights abuses within the Bank’s project areas and to prohibit reprisals against monitors, those that speak to them, or people that lodge complaints. The World Bank refused.

In 2015 and 2016 the World Bank said that it spoke with the Uzbek government about alleged reprisals. Nonetheless, reprisals continued and the Bank has not escalated its response.

The Way Forward for the Government of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan’s former authoritarian president, Islam Karimov, whose death was reported on September 2, 2016, left a legacy of repression following his 26-year rule. The country’s new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, promised increased accountability and acknowledged the lack of reform in key aspects of Uzbekistan’s society, including the economy and the criminal justice system. Despite these statements and the release of several political prisoners, Uzbekistan’s rights record remains atrocious. This leadership change provides a good moment for concerned governments and international financial institutions to press for comprehensive reforms to dismantle Uzbekistan’s forced labor system and provide accountability for past abuses.

Reform of the cotton sector, with its rampant corruption and abusive labor practices, would be a significant step in realizing Mirziyoyev’s promise of accountability. However, Mirziyoyev’s previous positions raise concerns about his credibility. As prime minister from 2003 to 2016 he oversaw the cotton production system, and as the previous governor of Jizzakh and Samarkand, he was in charge of two cotton-producing regions. The 2016 harvest, when Mirziyoyev was acting president and retained control over cotton production, continued to be defined by mass involuntary mobilization of workers under threat of penalty.

As this report outlines, the government can implement immediate reforms to show a real commitment to ending forced labor, including by significantly curtailing forced labor and eliminating child labor in the cotton sector, as well as implementing broader reforms in the agricultural sector to address the root causes of forced labor. Basic steps would includeenforcing laws that prohibit the use of forced and child labor, instructing government officials to stop coercing people to work, and allowing independent journalists and human rights defenders to freely monitor the cotton sector without fear of reprisals.

The Way Forward for the World Bank, International Finance Corporation

The World Bank should suspend disbursements in all agriculture and irrigation financing in Uzbekistan until the government fulfills its commitments under World Bank agreements not to utilize forced or child labor in areas where there are Bank-supported projects. The IFC should similarly suspend disbursements to investments in Uzbekistan’s cotton industry until its borrowers can show that they do not source cotton from fields taintedbyforced or child labor.

In addition, the World Bank and the IFC should take all necessary measures to prevent reprisals against monitors who document and report on labor conditions or other human rights issues linked, directly or indirectly, to their projects in Uzbekistan. The institutionsshould closely monitor for reprisals and, should they occur, respond promptly, publicly, and vigorously, including by pressing the government to investigate and hold to account anyone who uses force or threatens persons reporting human rights concerns. They should also independently investigate alleged violations and work to remedy harms suffered from reprisals.

In addition, the World Bank and IFC should publicly and regularly report on reprisals linked in any way to their investments, as well as the actions they took to respond. The Bank should amend its project agreements in Uzbekistan to require the government to allow independent journalists, human rights defenders, and other individuals and organizations access to monitor and report on forced and child labor, along with other human rights abuses in all World Bank Group project areas. The agreements should also require the government to ensure that no one faces reprisals for monitoring human rights violations in project areas, bringing complaints, or engaging with monitors.

Download the full REPORT.