AAN

The judges of the International Criminal Court’s Appeals Chamber are now deciding whether to authorise an investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly perpetrated in Afghanistan. The court’s Pre-Trial Chamber decided in April to reject such an investigation. At the appeal hearing, everyone who spoke agreed that crimes severe enough for the ICC to prosecute had been committed in Afghanistan. However, there were fierce arguments over whether they should be investigated by Afghanistan or the ICC, and whether the ICC could investigate alleged crimes committed by the United States citizens in Afghanistan or against Afghan citizens elsewhere. AAN’s Ehsan Qaane and Sari Kouvo were at the hearing in The Hague and here answer the five main, pressing questions raised.

1. Why did the ICC hold appeals hearing on Afghanistan?

The three full days of hearings by the International Criminal Court (ICC) Appeals Chamber (4-6 December 2019) were yet another step in the, by now, 12-year-long ICC-Afghanistan saga (see AAN’s previous reporting here). When in April 2019 the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber (Pre-Trial Chamber) rejected the Prosecutor’s request to open an investigation, the Pre-Trial Chamber clearly stated that crimes grave enough for the ICC to prosecute had indeed occurred in Afghanistan and that the relevant national governments were neither able nor willing to investigate the crimes (here is the decision in English, Pashto and Dari). The Pre-Trial Chamber’s decision not to authorise an investigation rejection was – controversially – based on its assessment that an investigation would not serve what the ICC statute calls “the interests of justice.” This term, as shall be discussed further on, is not defined in the ICC Statute, but is often considered to include both public and victims’ interests. The reasons the Pre-Trial Chamber gave for its assessment was that it would be too difficult to conduct investigations and that an unsuccessful investigation would hurt both victims’ expectations of justice and the legitimacy of the court.

The prosecutor and three legal representatives of victims (named in the ICC reportage, LRV1, LRV2 and LRV3) appealed the Pre-Trial Chamber’s April 2019 decision. In response, the Appeal Chamber held last week’s hearing to decide whether the Pre-Trial Chamber’s ruling should be overturned or upheld.

The Afghan government also made a submission. Additionally, 17 Afghan organisations and some experts submitted amicus curiea, legal arguments based on their expertise – and interests – which reminded the judges about what the ICC’s core legal documents, including the Rome Statute, say.

2. Which main questions were discussed during the hearing?

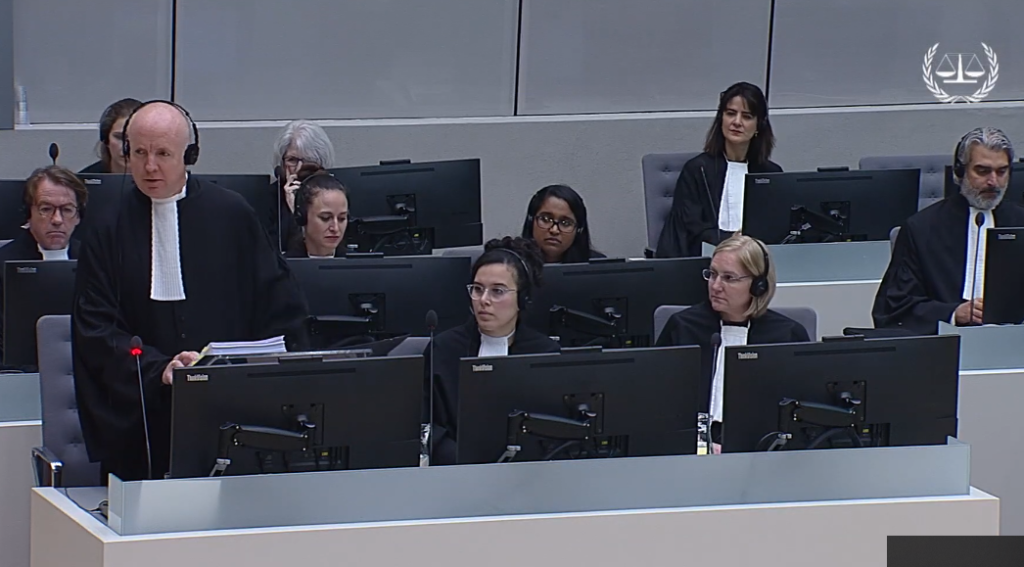

(Photo: Ehsan Qaane)

The appeals hearing focused on three sets of questions. First, it looked at whether ‘victims’ (in scare quotes because, at this stage, they are still alleged victims) had the right, in the first place, to appeal a decision by the Pre-Trial Chamber, and whether they could be considered parties to the appeals hearing. Second, it focused on whether the decision taken by the Pre-Trial Chamber concerned the ‘jurisdiction’ of the court, as this would have allowed the victims’ groups to appeal. Another related aspect was whether the Pre-Trial Chamber was right in how it had sought to restrict the actual investigation. Third, it focused on whether the Pre-Trial Chamber had the right to carry out an ‘interests of justice’ assessment and if it did, did it do so correctly? (1)

It was largely this third question – the ‘interests of justice’ assessment and whether the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber had the authority to interpret this term – that was at the heart of the hearing.

The first set of questions – whether the victims could appeal the Pre-Trial Chamber decision – was addressed during on the first day. After the three legal representatives of victims submitted their requests to appeal, the prosecutor responded by referring to Rome Statute article 82(1)(a) that only names the prosecutor as a party who can appeal. The Pre-Trial Chamber judges agreed with the prosecutor and argued that, at this stage, those who submitted representations to the ICC as victims, were not recognised as victims before the court; rather they are “potential victims” (full decision here).

Basically, what the Pre-Trial Chamber judges meant was, in the pre-trial phase, before actual investigations and prosecutions, the ICC can neither tie specific perpetrators nor specific victims to specific crimes. Therefore, there are no objectively identifiable victims who can make an appeal. Nevertheless, and regardless of the opinion of the prosecutor and the decision of the Pre-Trial Chamber judges, the Appeals Chamber judges did grant the Legal Representatives of Victims permission to submit their appeals brief. They said that, during the hearing, they would decide whether the Legal Representatives of Victims have the right to appeal or not. Three groups – referred to as LRV1 (on behalf of 82 victims), LRV2 (on behalf of four victims of United States torture) and LRV3 (on behalf of two victims of drones launched from Afghanistan, so-called ‘cross-border’ victims) – submitted their written appeals briefs and made oral statements on the first day of the hearing.

On the second day of the hearing, the Appeals Chamber judges announced that they had come to the same conclusion as the prosecutor and the Pre-Trial Chamber judges. They shared the opinion that the victims’ groups could not challenge the Pre-Trial Chamber decision, as they were not a party to the proceedings. One judge submitted a dissenting opinion, objecting both to the way the Appeals Chamber had reached its decision and its meagre argumentation (watch from 3:40 to 11:00). The judge argued that the Appeals Chamber should not have decided on the victims’ right to appeal orally and without proper legal justifications. Victims’ rights should never be a side issue for the court, she said, and nor should it have been dealt with without an in-depth legal assessment.

As a courtesy, the legal representatives of victims were allowed to remain present at the full proceedings and to respond at given times. One of the legal representatives told AAN (off-the-record) that she had expected such a decision from the Appeals Chamber judges as “there is no clear legal support in the ICC’s core legal documents for victims challenging the Pre-Trial Chamber judges’ decision at this stage.” Nevertheless, she was satisfied at having been given an opportunity to present victims’ views during the hearing.

The second set of questions related to whether the decision not to authorise an investigation could be considered as a decision related to the ICC’s jurisdiction within the meaning of article 82(1)(a) of the Rome Statute which says that “any party” may appeal “a decision with respect to jurisdiction or admissibility” of the court. According to one of the Legal Representatives of Victims (who asked not to be named), they had raised the issue of jurisdiction as this was the only way to support their argument that they should be a party to appeal. According to the source, this was why the prosecutor had reacted to the Legal Representatives of Victims’ request to appeal at a very early stage. This particular article of the Rome Statute does not usually apply to the phase before an actual decision about an investigation has been taken.

A second issue raised in this set of questions focused on the scope of a possible investigation. None of those, including the Legal Representatives of Victims, the prosecutor and the Afghan government representatives, who spoke at the hearing seemed to question the Pre-Trial Chamber’s original finding, that crimes that met the ICC gravity threshold had been committed in Afghanistan. The prosecutor and the Pre-Trial Chamber did, however, not agree on whether the incidents outlined in the prosecutor’s request to open an investigation was the full list of incidents to be investigated or just a sample. While this point may seem rather theoretical in a situation where the Pre-Trial Chamber has rejected the request to open an investigation, it has legal – and political – significance. The Prosecutor is obviously keen to be as free as possible in where the investigation takes her, and not having the Pre-Trial Chamber set limits for an investigation. Indeed, one of the main parts of the hearing was to address this conflict of power between the prosecutor and the Pre-Trial Chambers judges. Moreover, while the prosecutor’s preliminary examination found grounds for investigating the US and Afghan government forces for the alleged use of torture and the Taleban and other insurgent groups, for various crimes including murder and the intentionally attacking civilians. However, when victims were asked for their opinions on a possible ICC investigation in December 2017/January 2018, they produced a much longer list of crimes, including rape, enforced disappearance and enforced displacement (the identities of the alleged perpetrators were not released). (For more detail on the victims’ submissions, see AAN reporting here).

The third set of questions related to the merits of the appeals filed by the prosecutor and the victims, which mainly challenged the authority of the Pre-Trial Chamber to, first, interpret the ‘interests of justice’ and, second, limit the scope of an investigation to only the specific incidents mentioned in the prosecutor’s request submitted to the Pre-Trial Chamber. The hearing focused extensively on the notion of ‘the interests of justice’. Important questions for the hearing of the appeal were whether the Pre-Trial Chamber had exceeded its mandate in deciding that an investigation would not be in the interests of justice given what it thought was the low chance of success and whether this assessment had been right in the first place.

3. What were the positions of the various participants to the proceedings?

During the hearing, a panel of five judges, (2) different from the judges of the Pre-Trial Chamber, listened to the various arguments. First, they listened to the prosecutor and the legal representative of the Afghan government. (3) Then, the three separate groups of legal representatives of victims (LRV1, 2 and 3) were heard; they represented, respectively, the victims of war crimes in Afghanistan, Afghan victims of United States torture programmes, and Pakistani victims of drones sent by US forces in Afghanistan. The Office of the Public Council of Defense (OPCD), an independent office placed within the structures of the ICC, also spoke, although it did not have a strong presence at the hearing. (4) After that, the panel of judges listened to several experts and interested participants, the amicus curiea, who made so-called amicus submissions to the court. These are independent submissions that seek to help the court in its deliberations. Most notably, amicus briefs were submitted, amongst others, by: a number of Afghan human rights and victims groups, including five members of the Transitional Justice Coordination Group (TJCG); the European Centre for Law and Justice, which is a conservative US-based think tank arguing against the ICC’s right to investigate alleged crimes committed by US citizens and; by Professor David Scheffer, who was US Ambassador at Large for War Crimes Issues (1997-2001) and at that time led the US delegation for the United Nations talks that resulted in the establishment of the International Criminal Court. (5)

The prosecutor’s main argument, in line with her written submission, was that the Pre-Trial Chamber had erred in the law, firstly, “by seeking to make a positive determination of the interests of justice.” In other words, as prosecutor, she does not need to show that an investigation is in the interests of justice in accordance to the ICC statute article 53, but should be authorised to proceed with an investigation unless there are compelling reasons that a prosecution would not serve the interests of justice. She also argued that the Pre-Trial Chamber had abused “its discretion in assessing the interests of justice.” She contended that the Pre-Trial Chamber has no role to play in assessing the ‘interest of justice’, unless the prosecutor has decided that a case is not in the interest of justice. On the last day of the hearing, the prosecutor requested the Appeals Chamber judges to either authorise a full investigation in Afghanistan itself or to send the case back to the Pre-Trial Chamber, to instruct the Pre-Trial Chamber to authorise an investigation immediately.

The Afghan government in its submission agreed that grave international crimes had been committed on its territory since the ICC’s jurisdiction came into force, but strongly rejected the notion that it was unwilling to prosecute these crimes. It built its arguments along two lines: 1) its representatives argued, as the Pre-Trial Chamber judges had done, that an ICC intervention would not serve the interests of justice, as it could jeopardise the ‘peace process’, and 2) it challenged the admissibility of the ICC by providing evidence of a new law and institutional developments in the country, to prove it was willing to deal with war crimes and crimes against humanity. Despite the apparent contradictions in this argument (more on this below), the government suggested that it was best placed to decide when prosecutions made sense, given a context both of insecurity and an ongoing peace process, but that Afghanistan did now have the capacity to investigate and prosecute. The government provided just one lone example of ongoing domestic proceedings: the investigation of an incident in Zurmat in December 2018 where six civilians were killed allegedly by the CIA-supported Afghan Khost Protection Force (more details about these killings in AAN’s reporting here).

The Office of the Prosecutor and the Legal Representatives of Victims all challenged the government’s position by noting the internal contradiction in its argument. On one hand, it was saying that since Afghanistan can now prosecute domestically, there is no need for an ICC intervention, but on the other hand, the Afghan judiciary’s ability to prosecute was challenged by insecurity, since large parts of the country are not under government control and its judges and prosecutors are targeted by the Taleban. Another issue raised by the Office of the Prosecutor was that the government will have opportunities to challenge admissibility further along in the process.

Furthermore, in response to the government’s submission that new domestic developments that could ensure domestic prosecutions had not been considered by the court, the prosecutor said her office had been aware of these developments when it submitted its request to authorise a full investigation. She said that, although the steps taken by the government towards seeking to ensure proper investigations were positive, they are not enough to ensure prosecutions. She said the government should have provided evidence to show it was already dealing with cases.

The Legal Representatives of Victims challenged the Pre-Trial Chamber decision by arguing that the commencement of a full investigation was, in fact, in favour of the interests of justice. It stated that the Pre-Trial Chamber had erred in procedure, law and fact by not authorising an investigation in Afghanistan based on an assessment of the interests of justice. For example, the LRV1, in line with its written submission, provided six grounds for appeals. In its first ground, LRV1 argued that even if the Pre-Trial Chamber had the authority to interpret the interests of justice, it should have consulted the prosecutor and the victims before making such a decision. Since it did not, the Pre-Trial Chamber had erred in the procedure. Its second, third and fifth grounds of appeal related to what it said were Pre-Trial Chamber errors in denying the request to authorise an investigation based on a lack of “state cooperation,” the unfeasibility of an investigation, and the need to “allocate” the Office of the Prosecutor’s resources to “other preliminary investigation [with more] realistic prospects to lead to trials.” These, it said, were errors in fact and law. The fourth and sixth grounds of appeal related to the restrictions on the scope of the investigation. In its fourth ground of appeal, LRV1 argued that the Pre-Trial Chamber, “by majority, erred in attempting to restrict the scope of any investigation which might be authorised in the future to incidents specifically mentioned in the prosecutor’s request, as well as those ‘compromised within the authorisation’s geographical, temporal, and contextual scope, or closely linked to it.’”

All of the Legal Representatives of Victims, on the last day of the hearing, requested the Appeals Chamber judges to authorise an investigation into the ‘Afghanistan situation’ without any restriction of scope. They argued that sending back the case to the Pre-Trial Chamber would be a step backwards. LRV2 and LRV3 also provided further details about their clients’ cases – none of which had been investigated domestically by states involved, in particular, the US – and stressed that the ICC investigation was the only hope for getting justice for their clients.

4. What were the main arguments by the experts and interested participants that addressed the Appeals Chamber?

The most interesting part of the hearing was listening to the different amicus curiae, ie, the experts and interested participants. These submissions and oral presentations clearly showed the diversity views and conflicting interests with regard to a possible ICC investigation in Afghanistan and how such an investigation would have implications not just for Afghanistan, but also the future of the ICC, itself. The amici brought three distinct issues to the fore: first, the raison d’être and basic principles of the ICC; second, the question whether the ICC is a victim-centred court, or not, and what that means for its engagement in Afghanistan and; finally, whether the ICC has any business investigating the alleged crimes of US citizens (when their country is not a member of the ICC).

The first issue – the raison d’être of the court – was mainly raised by amici who had come to the hearing shocked by the fact that the Pre-Trial Chamber had carried an interests of justice assessment and, moreover, one that focused on whether the prosecutions would be successful or not.

Professor David J Scheffer, who had represented the US in the drafting of the Rome Statute, focused his presentation on the intention of the drafters of the Rome Statute. According to him, based on the Rome Statute article 53, a Pre-Trial Chamber is not authorised to carry out a positive interests of justice assessment, especially not when the prosecutor has not in any way questioned whether an investigation would be in the interests of justice. That is, the Rome Statute only demands that the prosecutor engages on the interests of justice when a case is not in the interests of justice and the Office of the Prosecutor’s role may only be to review a negative ‘interests of justice’ assessment. Scheffer admitted, though, that the drafters had chosen not to define ‘interests of justice’ because there were almost as many interpretations of this notion as there were state parties. However, as he said, “justice is justice” and if war crimes prosecutions were only done when they were considered likely to succeed, there would have been few war crimes tribunals.

Scheffer’s point was further developed by the representative of Global Rights Compliance, an international law firm, that had conducted an empirical study on the interests of justice. The representative noted that they had found two basic approaches: mandatory prosecutions and opportunistic prosecutions. The main principle in the Rome Statute, he said, is mandatory prosecutions, ie if the basic reasons for prosecutions are fulfilled (threshold and complementarity), investigations should start.

The second issue was raised mainly by the amici representing the 17 Afghan human rights and victims organisations who had surveyed and interviewed “hundreds of victims” in the “three months” before the hearing in order to provide their direct voice in the amicus curiae submission. The representatives argued that the Pre-Trial Chamber had ignored the victims’ interests and their wishes for an ICC investigation in its April 2019 decision and that the decision was made based on an “uncited and unreasoned conclusion [which] is pure speculation.” The group believed that the Pre-Trial Chamber decision had created “frustration and hostility” toward the ICC and “has brought this very institution to the precipice of failure and caused serious questions as to its legitimacy, credibility, and ability to bring justice.” The group told the Appeals Chambers judges they had the opportunity to “correct the court’s course” (For full statement watch from 3:20-18:59 of the video).

The third issue was raised by the amici who were at the ICC mainly to reiterate that the ICC had no right to investigate alleged crimes committed by US citizens or against Afghan citizens abroad. Jay Alan Sekulow of the European Centre for Law and Justice, a conservative, US-based human rights think tank, based his oral presentation on the fact that the US was not a signatory to the Rome Statute and had taken a principled stance against it ever since the drafting of the Statute and the inception of the court. He drew on basic principles of customary international law and the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties to make the point that a government cannot be bound by treaty law unless it has expressly agreed to it, or at the very least cannot be bound by treaty law if it has consistently objected to it. He also responded to the prosecutor’s claim that the ICC had jurisdiction since the Afghan government had ceded jurisdiction to the court when it signed the Rome Statute in 2003, arguing that the Afghan government did not, at that point, have jurisdiction over US forces since the bilateral Status of Forces agreements expressly provided the American military “immunity” from prosecutions in Afghanistan. The latest bilateral agreement, signed in 2014, repeated the provision in the 2003 document that the US has the “exclusive right to exercise jurisdiction” over US servicemen and women and those in the ‘civilian component’, ie contractors employed by the US department of defence and that they will not be detained or handed over to any “international tribunal” (article 13). (See AAN’s reporting about the agreements here).

Before the hearing of the appeal, there were rumours that the Afghan government, instead of engaging in the proceedings, might decide to withdraw from the Rome Statute. A few countries, such as Burundi in October 2017, have already withdrawn from the court, complaining that the ICC meddles in national politics and peace processes. However, it chose not to. Even if it had withdrawn, the decision would have only come into force one year after the date of submission. Instead, the Afghan government decided to engage with the court, arguing that it was now able to prosecute and that the ICC did not, therefore, have jurisdiction (contested by both prosecutor and victims’ legal representatives).

Judges, experts, legal representatives of victims and of the Afghan government meet to argue for and against or to make a decision on whether an investigation should be authorised into alleged war crimes committed in Afghanistan. (Photo: International Criminal Court, 2019)

As a side note, it is worth mentioning that the Appeals Chamber hearing was held in parallel – although completely independently of – the meeting of the Assembly of the State Parties of the Rome Statute. This is an annual meeting at which all 124 state parties to the Rome Statute come together to discuss the ICC performance, budget, and developments within it. There was also an important civil society presence at the assembly, the majority of which (including the Afghan civil society presence) came under the umbrella of the Coalition for the International Criminal Court. One of the key questions at this year’s assembly was a review of the ICC which had been prompted, among other reasons, by the extremely slow process with which the ICC had engaged in Afghanistan (the prosecutor began her ‘preliminary examination’ in 2006 and only asked the court to authorise a full investigation a decade later), as well as the relative failure of the ICC to engage with victims and carry out outreach (more on the court outreach see AAN’s reporting here and here).

5. What happens next?

It is now up to the Appeals Chamber to ponder what the next step should be for the ICC in Afghanistan. In terms of timing, the judges of the ICC approved a regulation in November 2019 in which they agreed that a chamber’s decision should be finalised within four months of the notification of the prosecutor’s request, including appeal request (pursuant to article 15 of the Rome Statute). This means the Appeal Chamber judges should come up with a decision on Afghanistan no later than 7 April 2020. However, the judges may not be able to make their decision on time, given the complexity of this case. Talking to interlocutors in The Hague, including the ICC’s Outreach Office, there has been no indication whether the decision will come quickly, or whether the Appeals Chamber may seek to delay its decision. The ICC has already faced criticism that the Pre-Trial Chamber spent over a year pondering its decision not to allow the prosecutor to open an investigation. Some of those whom AAN spoke to thought the Appeals Chamber might seek to counter this criticism by taking a quick decision.

The engagement of the ICC in Afghanistan remains highly contentious and complicated. The Appeals Chamber will need to engage on the issue of the Pre-Trial Chamber’s positive interests of justice assessment, and it will most likely also need to engage with the question of what the interest of justice should mean for a court of last resort. It will also be interesting to see how and to what extent the Appeals Chamber engages with the question of whether the prosecutor can investigate crimes allegedly committed by US citizens in Afghanistan or against Afghan citizens abroad. While the argument that the US has not signed the Rome Statute and therefore cannot be bound by the treaty is convincing, the ICC was established exactly to address those crimes that should never be beyond the reach of the law.

The US is likely to continue its systematic objection and bullying of the court. The Afghan government is likely to continue to try to convince the ICC that it is able and willing to prosecute – and also that it is best placed to decide on the timing of possible investigations given insecurity and a possible peace process. Some of the points raised by the Afghan government will resonate with other state parties, who may silently agree that an ICC engagement in the pre-peace negotiation phases is, if not objectionable, then at least complicated. These may be some of the reasons why the court may want to stall its decision.

In terms of the content of the decision, there are three main options for the Appeals Chamber:

First, it could simply uphold the decision taken by the Pre-Trial Chamber and reject the prosecutor’s request to open an investigation into the situation in Afghanistan. The rejection can be done on the same, or on different grounds than those raised by the Pre-Trial Chamber. However, regardless of what grounds the court chooses, it will need to engage with the key questions of whether Afghanistan is able and willing to prosecute nationally, and whether the Pre-Trial Chamber was right to conclude that an ICC investigation would not be in the interests of justice, even though almost all the victims who submitted views overwhelmingly said they wanted an investigation. The Office of the Prosecutor could also still collect new facts and submit a new application to the Pre-Trial Chamber to start an investigation. In that case, the Afghanistan file will need to return to the preliminary examination process.

Second, the Appeals Chamber could send the case back to the same, or to a new Pre-Trial Chamber. In this case, the Appeals Chamber may ask for an immediate authorisation of an investigation, or it may highlight the errors in law made by the Pre-Trial Chamber and ask it to reverse its decision after considering these errors, and to take a new decision. The decision could again be a negative one, but taken on different grounds. If the new decision of the Pre-Trial Chamber still did not satisfy the prosecutor, she could again appeal.

Third, the Appeals Chamber could authorise the prosecutor to begin the investigation in Afghanistan. Here, the Chamber would need to engage with the question of whether, or to what extent, the Afghan government is itself willing and able to prosecute. However, it is clear that, even if the ICC does decide to open an investigation, the road to a successful prosecution of international crimes in Afghanistan would still be long and difficult.

Edited by Martine van Bijlert and Kate Clark

(1) The following legal wording was used for the three issues:

Group A: Standing of victims to bring an appeal under article 82(1)(a) of the Rome Statute: (a) Should victims be considered parties in the proceedings under article 15 of the Rome Statute in comparisons to other phases of the criminal proceedings? (b) The victims submit that a decision under article 15(4) is a decision with respect to jurisdiction within the meaning of article 82(1)(a) of the Rome Statute. Is the right to appeal a decision with respect to jurisdiction (last sentence of article 19(6) of the Rome Statute) limited to those who may challenge the Court’s jurisdiction (article19(2)) or seek a ruling on jurisdiction (first sentence of article 19(3) of the Rome Statute)? (c) Does the right of victims to make representations under article 15(3) of the Rome Statute entitle them to appeal the decision pursuant to article 15(4) of the Rome Statute? (d) In light of article 21(3) of the Rome Statute, do the internationally recognised human rights of access to justice and obtain an effective remedy for human rights violations entail a right for victims to appeal a decision that rejects a request under article 15(4) of the Rome Statute?

Group B: Whether the Impugned Decision is one that may be considered to be a ‘decision with respect to jurisdiction’ within the meaning of article 82(1)(a) of the Rome Statute: (a) Having regard to the existing jurisprudence of the Appeal Chamber, can the Impugned Decision be said to be a decision with respect to jurisdiction? (b) The victims argue that decisions with respect to the exercise of jurisdiction may be appealed as decisions with respect to jurisdiction under article 82(1)(a) of the [Rome] Statute. Article 5 of the [Rome] Statute enumerates the crimes falling under the Court’s material jurisdiction, while articles 12 and 13 indicate with when and how the Court’s jurisdiction can be exercised. In interpreting the wording ‘decision with respect to jurisdiction’, would such wording include decisions making determinations on the pre-conditions to the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction under article 12 or the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction under article 13 of the [Rome] Statute? (c) Pre-Trial Chamber II limited the scope of the investigation to incidents specifically mentioned in the prosecutor’s request and authorized by the Chamber. Could this aspect of the Impugned Decision be considered to be a determination with respect to jurisdiction?

Group C: Merits of the appeals filed by the Prosecutor and the victims: (a) When the Prosecutor requests authorisation to initiate an investigation having considered article 53(1)(c) of the Statute, does the pre-trial chamber have the power to consider the factors under article 53(1)(c) of the Statute itself? (b) Are the factors considered by Pre-Trial Chamber II at paragraphs 91 to 95 of the Impugned Decision when determining that the authorisation of an investigation would not be in the interests of justice appropriate factors for such a determination? (c) in deciding where to authorise an investigation, may a Pre-Trial Chamber limit the scope of the investigation to incidents specifically mentioned in the Prosecutor’s request and authorised by the chamber?

For the different articles in the Rome Statute mentioned by the Appeals Chamber, see the Rome Statute.

Article 53 that relates to the much-discussed notion of the interests of justice, is reproduced here: Initiation of an investigation1. The Prosecutor shall, having evaluated the information made available to him or her, initiate an investigation unless he or she determines that there is no reasonable basis to proceed under this Statute. In deciding whether to initiate an investigation, the Prosecutor shall consider whether:

(a) The information available to the Prosecutor provides a reasonable basis to believe that a crime within the jurisdiction of the court has been or is being committed;

(b) The case is or would be admissible under article 17; and

(c) Taking into account the gravity of the crime and the interests of victims, there are nonetheless

substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice.

If the Prosecutor determines that there is no reasonable basis to proceed and his or her determination is based solely on subparagraph (c) above, he or she shall inform the Pre-Trial Chamber.

- If, upon investigation, the Prosecutor concludes that there is not a sufficient basis for a prosecution because:

(a) There is not a sufficient legal or factual basis to seek a warrant or summons under article 58;

(b) The case is inadmissible under article 17; or

(c) A prosecution is not in the interests of justice, taking into account all the circumstances, including the gravity of the crime, the interests of victims and the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator, and his or her role in the alleged crime; the Prosecutor shall inform the Pre-Trial Chamber and the State making a referral under article 14 or the

Security Council in a case under article 13, paragraph (b), of his or her conclusion and the reasons for the conclusion.

- (a) At the request of the State making a referral under article 14 or the Security Council under article 13, paragraph (b), the Pre-Trial Chamber may review a decision of the Prosecutor under paragraph 1 or 2 not to proceed and may request the Prosecutor to reconsider that decision.

(b) In addition, the Pre-Trial Chamber may, on its own initiative, review a decision of the Prosecutor not to proceed if it is based solely on paragraph 1 (c) or 2 (c). In such a case, the decision of the Prosecutor shall be effective only if confirmed by the Pre-Trial Chamber.

- The Prosecutor may, at any time, reconsider a decision whether to initiate an investigation or prosecution based on new facts or information.

(2) The panel of judges of the ICC Appeals Chamber consisted of Judge Piotr Hofmański (Presiding Judge), Judge Howard Morrison, Judge Luz del Carmen Ibáñez Carranza, Judge Solomy Balungi Bossa and Judge Kimberly Prost.

(3) The prosecutor team consisted of the Office of the Prosecutor, the Director of Prosecutions Division (Fabricio Guariglia), three appeals counsels and the Prosecutor Advisor for Trial. The legal representative of the Afghan government was London lawyer Rodney Dixon. The Afghan Ambassador to the Netherlands, Humayun Azizi, also addressed the court.

(4) The three different Legal Representatives of Victims were:

LRV 1: Mr Fergal Gaynor representing 82 victims;

LRV 2 consisting of three separate teams representing different groups of Afghan victims of US torture programs (specifically, Katherine Gallagher represented two victims, Margaret Satterthwaite represented three victims, Nikki Reisch, Tim Maloney and Megan Hirst represented two victims, and Nancy Hollander and Mikolaj Petrzak represented one victim);

LRV3: Steven Powles and Conor McCarthy representing the so-called ‘cross-border victims’, ie, Pakistani victims of cross-border drone strikes.

(5) The full list of the those who submitted amicus briefs is: Ms Spojmie Nasiri (and her team members Nema and Nasrina on behalf of Afghan human rights organisations), Mr Luke Moffett, Mr David J. Scheffer, Ms Jennifer Trahan, Ms Hannah R. Garry (on behalf of UN special reporters), Mr Goran Sluiter, Mr Kai Ambos, Mr Dimitris Christopoulos, Ms Lucy Claridge, Mr Gabor Rona, Mr Steven Kay, Mr Pawel Wilinski, Ms Nina H. B. Jorgenson, Mr Wayne Jordash, and Mr Jay Alan Sekulow.