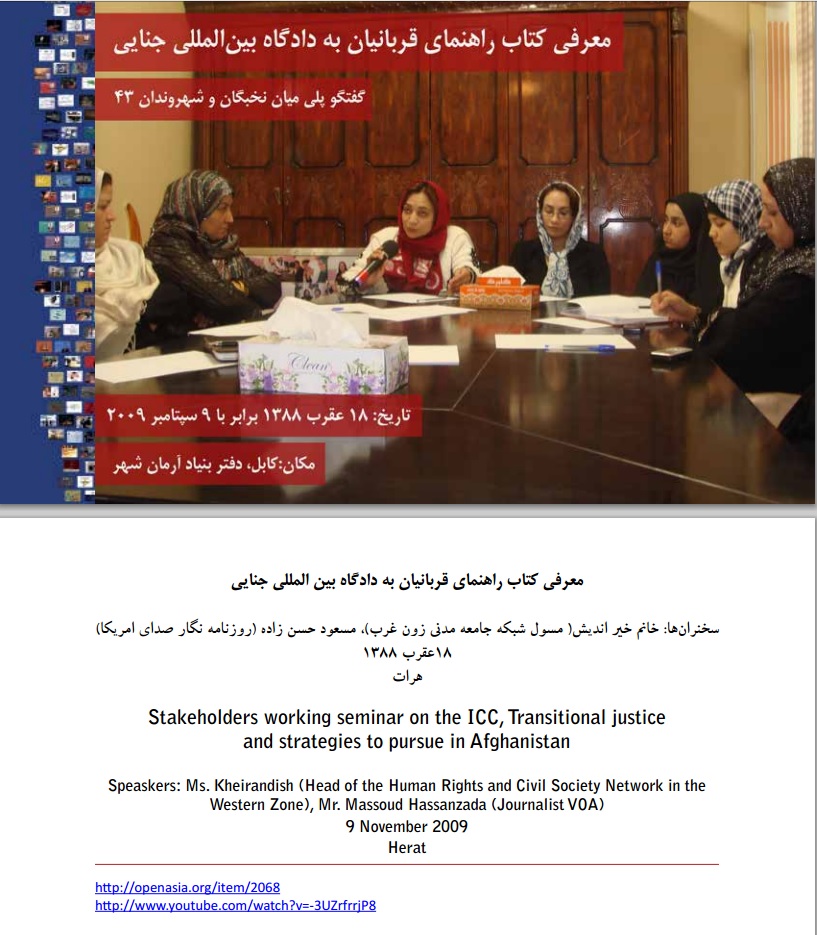

The city of Herat hosted the 43rd Goftegu public debate of Armanshahr Foundation on 9 November 2009 to also mark the publication of the new book, A Guideline for Victims to the International Criminal Court. The meeting, as a part of the series of public debates as a “Bridge between the Elite and the Citizens”, was the fifth of its kind to be held in this city, where 60 participants from civil institutions, human rights and citizenry activists, students and intellectuals took part. At the start of the meeting, the moderator, Rooholamin Amini, made a reference to the Simorgh Literary Prize, which the Armanshahr Foundation has organised to mark the International Day of Peace in the framework of its justice-seeking activities. Subsequently, he introduced the Armanshahr Foundation Guideline for the Victims to the ICC, and printed by the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.

The meeting consisted in the main part of a free debate about two basic issues related to TJ in Afghanistan, in which a considerable number of participants took part. Those two issues were: 1) How can we fulfil TJ? and 2) How should crimes against women be considered in the process of TJ?

Subsequently, Ms. Aziza Khayrandish, head of the Civil Society and Human Rights Network in Herat and Mr. Massoud Hassanzada, a young activist of citizenry rights, addressed the issues of Transitional Justice (TJ) and peace projects in Afghanistan.

The statute of the International Criminal Court has addressed these two issues. Indeed, the ICC is a mechanism to fulfil TJ throughout the world. There is a chapter, which specifically deals with crimes against women and children during war.

Mr. Hassanzada pointed out the challenge the ICC is facing in regard to the contradiction between its statute and the Afghanistan national laws. He said: “We have to see first where the laws of the ICC stand in relation to our laws.” He reminded that it is nothing new to pay attention to justice and the pursuit for it. It has existed in history and one may trace it in law books and religious teachings. He described TJ as obtaining justice through civil action, arguing that TJ could be a strategy for peace. “We can think of transitional justice in order to fulfil peace.” This concern has indeed been noted in the book. Pointing out the slow progress of TJ in Afghanistan, Mr. Hassanzada added: “The issue has heated up at several specific periods of time, but it has rarely been pursued in a systematic manner. A question of of such great importance should not be an occasional issue.”

Kabir Ahmad Salehi, another participant, said: “We should seek ways of materialising TJ in Afghanistan and see if it is possible to enforce it here. We have to think of fulfilling TJ in order to prevent the culture of impunity taking deeper roots in our country. Is that possible in our country? We need to take certain remedies. To materialise it, we need to enhance the rule of law and government building. We have to uproot administrative corruption.”

Ms. Shabnam Simia who appeared to share Mr. Salehi’s opinion, commented on fulfilment of TJ in Afghanistan: “We need to create the proper channels for Transitional Justice. As a first step, we have to purge the government to enable it to bring war criminals to court. Criminals within the government structure are growing more powerful everyday, just like parasites that feed from the host body. We need culture building and winning the people’s trust.”

Ms. Massoudeh Karkhi, a social activist, took a more dismayed attitude toward fulfilment of TJ: “The same people, who oppressed the people of Afghanistan yesterday, enjoy the support of their own ethnic group today. In a society where the people take that attitude toward war criminals, Transitional Justice will have a difficult task to succeed. I believe we will not succeed in achieving TJ, no matter how hard we try.”

Mr. Mozaffari, another participant, noted: “Our historical experience has sown distrust among the people. Our people have not come to believe yet that somebody from a different ethnic group could fulfil their wishes. That is why they support persons who may be disreputable persons. Tribalism, like it or not, is a deeply rooted issue in Afghanistan. In my opinion, we cannot fulfil TJ if we do not go through this phase.”

Ms. Aziza Khayrandish more optimistically considered the mechanisms for enforcement of TJ to be at our own disposal: “The aim of enforcing Transitional Justice is to introduce peace and justice in a country. Mechanisms to achieve it are not ready made for all countries alike. We should see how we can achieve TJ in our own country.”

Ms. Karima Hosseini, director of publications and publicity of Women’s Affairs Department of the HeratProvince, said she believed that TJ must be enforced in Afghanistan as of immediate effect, however: “It would only be possible to enforce TJ in Afghanistan if the people believe in it. We must give the courage to our people to defend their own rights.”

Ms. Nila Akbari, correspondent of the BBC Radio, offered her opinion: “I believe it is now too late to discuss if TJ is suitable for us or not. We have started on that road. The present government is not quite powerful, but it can do something about Transitional Justice. I do not believe the government to be incapable. I believe the government should convey the meaning of Transitional justice to the people first and then encourage them to express themselves.”

Mohammad Moussa Rezayi, a cleric, said: “If we concentrate the discussion around the following three issues, we will be able to reach a conclusion: 1) obstacles ahead of TJ; 2) what are the mechanisms available despite those obstacles? 3) preventing politicisation of this process,” adding that “of course, the circumstances for bringing up the issue are also important.”

Mr. Rezayi pointed out the breadth of the atrocities, referring to the reigns of the Marxists, the Mujahedin and the Taliban and offered the following mechanisms to fulfil transitional justice in Afghanistan: enhancing the civil institutions; properly defining TJ among social and civil institutions; not contrasting peace to justice; culture building; publicising the quest for justice through the media.

Mr. Tavakoli, another clerical participant, stated: “Pretenders to Transitional justice are occasionally the very accused. If we were to realise TJ, which is a possibility like many other concepts, we should know that we all have to rise to the occasion.” Alluding to Mr. Rezayi’s views, he said: “The other concern that was raised is universal. Universalising the issue is giving the wrong direction. In my opinion, we have to start at 1 if we cannot start at 100. Justice is occasionally pitted against peace. To achieve something, we have to give up something. If we cannot really appreciate the value of justice in our society, there is nothing wrong with giving our blood again.”

At the conclusion of the meeting, the guests were each presented a copy of the Guideline forVictims to the International Criminal Courtas well as copies of six other books of Armanshahr publications.

For more details on the publication, click HERE

For the video of the presentation, clicke HERE (Youtube)