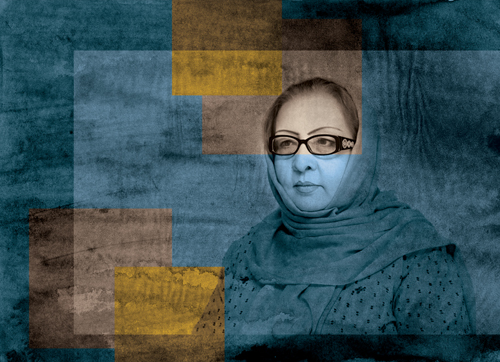

Najiba Ayubi is a journalist and activist for human rights and freedom of the press. She is the Director of the Killid Group, a non-profit Afghan media network encompassing press, radio, and online outlets with a national reach. Ayubi left Afghanistan with her family when the Taliban seized Kabul in 1996. She took refuge in Iran where she established a school for Afghan refugee children. When the Taliban fell in 2001, Ayubi turned down an opportunity to migrate to Europe, and rather returned to Afghanistan, where she worked first for Save the Children, and then joined the Killid Group as managing director. She is also a board member of the NGO Development and Humanitarian Services for Afghanistan. Ayubi was awarded the Courage in Journalism Award for 2013 by the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Can you share with us some memories of occasions when your rights have been violated?

I have received many serious threats because of my work as a journalist. My worst memory would have to be one night in 2007 when I was at home alone with my brother. A plastic bag with stones and a letter threatening my sister Najla and I was thrown into my house. The letter demanded that I stop my reports.

There was another time when I was working on a report about a police officer shooting a Grade 11 student. My reporter was on the scene before the Chief of Police had arrived. The police threatened him and seized his camera. My reporter called and asked what he should do. I told him to use his mobile phone so that we could broadcast live. A few minutes later, the Chief of Police called. He used my first name and asked me not to broadcast the report. He added, “You do realise that you are a woman?” I refused to submit to his gender-based intimidations. I told him, mirroring his condescending tone and addressing him by his first name, that I would broadcast the report as many times as I wished.

What are some important achievements in Afghanistan since the time of the Taliban?

Women have left a completely silent and non-participatory era behind them, and stepped into an era of extensive participation in political and social affairs. The increase in the number of school students, both girls and boys, is unprecedented in the history of Afghanistan. Furthermore, telecommunications and information technology are now extensively available: there are 22 million SIM cards used amongst a population of 30 million people. That is extraordinary in this region.

What gives you hope for the future?

The development of freedom of speech in Afghanistan. We have never seen anything like this before in our country, and even in comparison with other Asian countries, we are doing very well. This is a promising beginning.

What is your worst fear today?

Journalists and human rights activists face serious risks without adequate security. And I’m very conscious of the fragility of our achievements in the past 12 years. They are the result of 12 years of hard work and endeavours; I do not want to see them lost.

What are the biggest challenges facing Afghanistan?

We do not have well-balanced and complementary mechanisms in place to be able to achieve sustainable progress, both in the cultural and economic spheres. The interference by foreign countries in Afghan affairs and the presence of nuclear weapons in neighbouring countries in our region are other challenges.

Can you tell us about any specific occasions where the human rights of a female family member or friend were violated?

A few days before the most recent Loya Jirga [traditional grand assembly], my sister Najla participated in a roundtable discussion on TV. She made some very controversial comments and as a result, she was no longer allowed to go to the Loya Jirga.

What are some factors which deter women from participating in social, economic, political and cultural spheres?

Reprehensible traditions and inappropriate beliefs and attitudes about women are the major barrier. So long as women are seen as commodities rather than people, there is no place for women’s rights.

Our generation has made enormous sacrifices to fight for their rights, much more so than in previous generations. If our mothers had fought in this way, we would be in better conditions now. But nonetheless, today’s women are still not doing enough to break the chains that bar their participation.

What changes are necessary to advance women’s rights in Afghanistan?

Men and women must be viewed and treated equally within the family and in society. In particular, they must enjoy equal opportunities to education. There are still some areas in the country where you will find boys’ schools but not girls’ schools.

We need to combat illiteracy. If every literate woman in Afghanistan taught one illiterate woman to read by 8 March next year [International Women’s Day], and repeated this every year, we would, I believe, uproot illiteracy among women within five years.

How can societal institutions better support women’s rights?

Educated religious leaders should work together to highlight the role of women, and the government should develop laws and mechanisms that promote and defend women’s rights.

What have you done in your private or public domains to eliminate discrimination against women?

In my private domain, I’ve been fortunate not to face any problems. In the public domain, I have helped to recruit and educate women, and empower them not to depend on others but to be self-sufficient. Our policy at the Killid Group is that at least 40% of our staff must be women.

“Unveiling Afghanistan, the Unheard Voices of Progress” is a campaign by Armanshahr and FIDH, which explores views held by Afghan civil society actors. Over 50 days, 50 influential social, political, and cultural actors hope to spark conversation and debate about building a society that is inclusive of women’s and human rights in Afghanistan.

Follow 50 interviews drawn from the “Unveiling Afghanistan campaign” daily on the Huffington Post.

Follow Unveiling Afghanistan on FIDH Twitter: www.twitter.com/fidh_en