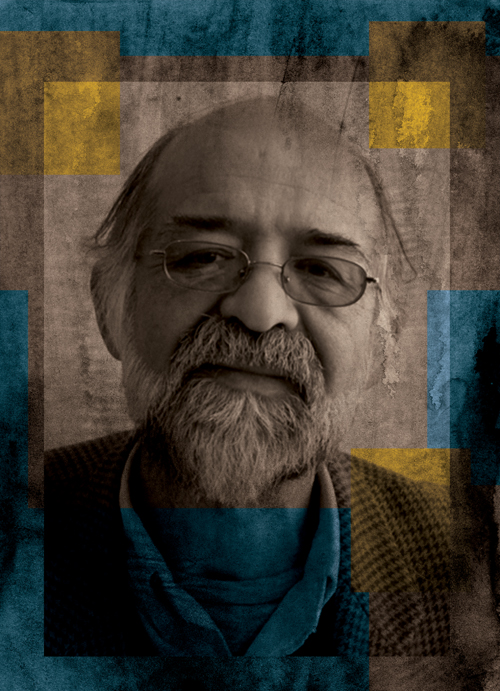

Sayed-Askar Mousavi was born in 1956. He has spent much of his life in exile. He went to high school in Iran, lived in exile in India and Pakistan, and received a Master’s Degree and a doctorate from the University of Oxford, where he was a senior member of St Antony’s College. He has been a political activist since the age of 14 and a prominent figure in exile of the “cultural struggle” during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. He formerly served as a senior adviser in Afghanistan’s Ministry of Higher Education. He has written extensively and is the author of ‘The Hazaras of Afghanistan: An Historical, Cultural, Economic, and Political Study’, published in 2009 by the University of Cambridge.

Can you share with us some memories of instances when your rights have been violated and how they have influenced your life?

I was an A-grade student and one of the best students in Kabul when I was in the 7th and 8th grade. Then in the 9th grade, I failed because I had problems in my Arabic classes due to my political activity. I was a Muslim alright, but I had issues with the reactionary methods. One of our Arabic teachers, who was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, gave me 3 out of 20, even though my Arabic was much better than his. Then there was another teacher who was a member of the Parcham party [one of the communist parties] who gave me an 8 out of 20 in another subject, believing that I was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood! And all the while, the Arabic teacher though I was a member of the Parcham party! These attitudes destroyed my youthful and enthusiastic approach towards my studies.

I lived for a long time in exile as a refugee during the Soviet occupation and the wars. One of my worst memories from this time is when I tried to go to Denmark. I was doing research for my doctorate at the time and had been invited by a Danish university. When I went to the Danish Embassy with my refugee travel papers, the official said that he could not issue me a visa. I asked him why and he replied: “Because you have no state, no political identity”. Those words broke me. It was one of the hardest moments of my entire period of exile.

What are the most important achievements in present-day Afghanistan?

One of the most important achievements of the past 40 years is the development of freedom of expression. It is at an unprecedented level, even within a system intertwined with despotism, discrimination, and corruption.

Another achievement is popular support for education. We have never seen so many people rushing towards opportunities for education. I am sure it will create fundamental changes in our future.

Finally, we have never before seen such a proliferation of free media outside the government’s monopoly.

What gives you hope for the future?

Freedom of expression. However, is this freedom truly alive? Freedom of expression is not something that should be ‘given’ to you. In other countries, in contrast to Afghanistan, people have won their freedoms by enduring sacrifices, bearing the heavy costs of imprisonment and executions of thousands of intellectuals.

What do you fear most today?

My greatest fear is that the reactionaries might go wild again. They are still there. There has been a discourse about a ‘good Taliban’ and a ‘bad Taliban’ for some time now. The ‘good Taliban’ is President Karzai and the people around him. And you can see the bad Taliban for yourself. I worry that the reactionaries may come back violently. They have reformed and exist in different groupings and manifestations. The Taliban group is only one of the multiple facets of reactionaries that are active today.

Is it possible that girls could once again be banned from schools and women excluded from social participation, as was the case under the Taliban?

We call this an ‘achievement’, but it is an extremely fragile one, because the people did not play a role in earning it back for themselves. It’s something that has been achieved because of the presence of the Americans. Because people have not worked for this, they don’t genuinely own this achievement, and the true support for it within the Afghan society is weak at best.

What are the factors that limit women’s participation in social, economic, political and cultural spheres?

Our society is a very traditional one, where not only men are against women, but women are even against themselves. Illiteracy is an extremely important factor, as is the lack of a legal system that can adequately deal with discrimination and exclusion.

What are some priorities for change to advance women’s rights?

Support for women’s rights needs to exist in practice, not only on paper. We need to prepare the ground to facilitate the economic growth of women. Women must be supported adequately in order to participate in the economy. Furthermore, we must combat the cycle of illiteracy. Illiterate women raise illiterate, violent, and ignorant men.

What have you done in your personal and professional life to fight against obstacles to women’s participation in Afghanistan?

I have always been a teacher, even when I served in the Ministry of Higher Education for more than a decade. A major priority was to create as many opportunities for women as possible. Afghanistan needs educated women to combat reactionaries, despotism, and structures of dependence.

“Unveiling Afghanistan, the Unheard Voices of Progress” is a campaign by Armanshahr and FIDH, which explores views held by Afghan civil society actors. Over 50 days, 50 influential social, political, and cultural actors hope to spark conversation and debate about building a society that is inclusive of women’s and human rights in Afghanistan.

Follow 50 interviews drawn from the “Unveiling Afghanistan campaign” daily on the Huffington Post.

Follow Unveiling Afghanistan on FIDH Twitter: www.twitter.com/fidh_en