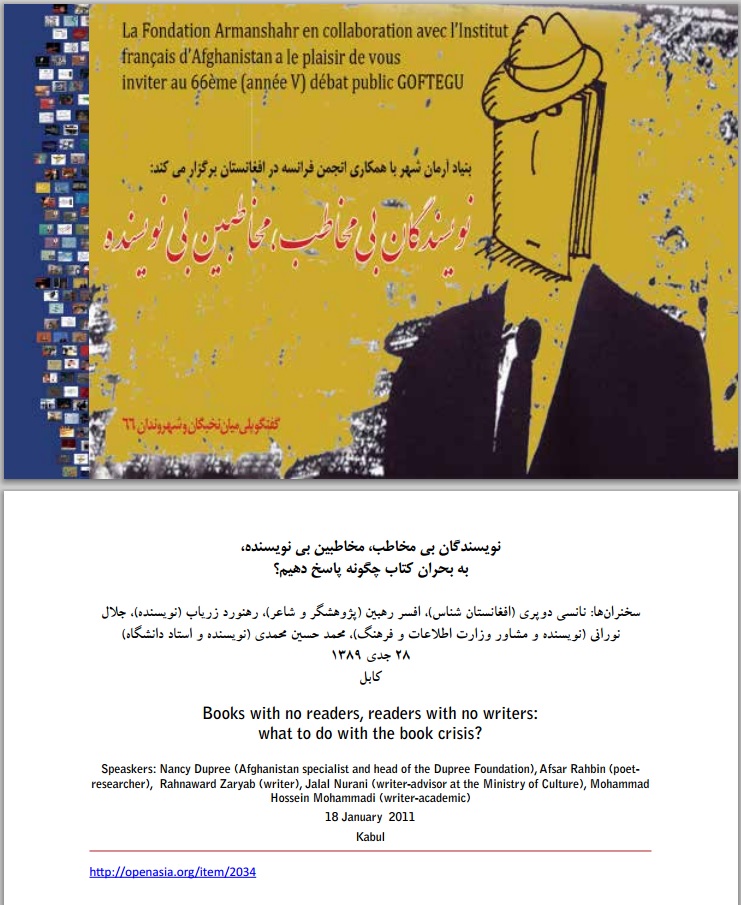

Armanshahr Foundation in collaboration with the French Institute of Afghanistan is pleased to invite you to its 66th (year V) public debate GOFTEGU on the occasion of Armanshahr’s SEVEN NEW publications

Speakers: Nancy Dupree (Afghanistan specialist and head of the Dupree Foundation), Afsar Rahbin (poet-researcher), Rahnaward Zaryab (writer), Jalal Nurani (writer-advisor at the Ministry of Culture), Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi (writer-academic),

Moderator: Rooholamin Amini

Date et Horaire/Date & Time: mardi/Tuesday 18 JAN. 2010, 14:00 H.

Lieu/Venue: Institut français d’Afghanistan (Lycée)/French Institute of Afghanistan

Tel: 0779217755 & 0775321697

E-mail: armanshahrfoundation.openasia@gmail.com

Books with no readers, readers with no writers

In the wake of the publication of 7 new titles in its series of publications, Armanshahr Foundation organised its 66th Goftegu public debate with the title of “Books with no readers, readers with no writers: what to do with the book crisis?” on 18 January 2011.

The Speakers were: Nancy Dupree (Afghanistan specialist and head of the Dupree Foundation), Afsar Rahbin (poet-researcher), Rahnaward Zaryab (writer), Jalal Nurani (writer-advisor at the Ministry of Culture), Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi (writer-advisor to Ministry of Culture), and Shiva Shargh (journalist). The meeting was held at the French Institute of Afghanistan.

This was the third public debate that Armanshahr Foundation had allocated to books and reading. The reports on the 18th public debate with the title of “Book, writing, reading” and the 26th public debate with the title of “Freedom of expression and civil responsibility; what separates the two?” have already been published in a single booklet.

The moderator was Mr. Rooholamin Amini (Armanshahr), who outlined the aim of the public debate as follows: Armanshahr Foundation has published more than 40,000 copies of books in the past five years. Seven new titles are available here for free. In meetings like this one, we can ask various questions and view the challenges in the society from different perspectives.

When we speak of culture, we have to refer to a long-term plan to guarantee our future. The government is investing in various fields, e.g. by advertising to recruit the young people to the army, the police etc. However, it could spend one percent of the cost of those advertisements to encourage young people to read books. Even the students have stopped reading. This is the reason why we have organised this public debate.

Nancy Dupree, as the first speaker, briefly reviewed the cultural-literary past of Afghanistan: There was a pleasant tendency to language and literature in Afghanistan in the past. The people of this land have paid special respect to great writers such as Khajeh Abdollah Ansari, Ferdowsi, Aysha Durrani and others. Mahmoud Tarzi was a writer at the turn of the last century who employed the power of language and literature in politics. A new generation came after him like some of the gentlemen who are sitting here. This generation managed to bring a change to the ruling structure of literature. Young writers coming after Mahmoud Tarzi went through difficult conditions. The political dealings that caused great damages in all fields left their impact on literature too. Fortunately, war could not destroy literature and writers. Migrant writers organised poetry reading, literary critique meetings in Peshawar and other places and prevented decline of literature. In the 90s when it was possible for writers to return to their country, the conditions were unfavourable for them. There have been considerable events in the past 10 years. The Afghans are now using every opportunity properly. There have been great achievements in the pas few years. Books are published in Mazar, Herat and Kandahar, where publishing books would have been unbelievable. We are now witnessing books with good design and good layout. There are bookshops within Afghanistan now. Bookshops and libraries did not have clients in the past, but they do now. The greatest challenge in Afghanistan concerns readers of literary works. Special attention should be paid to the creation of literary works.

Master Zaryab began by reciting a verse from Hafez, who had complained of the people and wanted to take his pearl elsewhere. He said: Hafez complained of the people of his age, who did not value him. Nevertheless, he was one of the few who gained a reputation in his life and his sonnets went beyond Shiraz and reached our cultural domain. Hafez also said in a verse that his reputation had reached the people of Egypt, China, Rome and Rey.

Who were Hafez’s audience? In the first place, the royal courts and their entourage valued his pearl; then the Dervishes and the scholars. The khaneqahs (Sufi centres) were indeed promoters of literary culture among the lower people. It is not surprising that almost all our poets were Gnostics in the fifth century. It is a pity that many great literary-cultural works that did not have a mystical air were shelved, e.g. the Bayhaqi History. It was only in 1862, after the British orientalist M. Morley published it, when the attention of our scholars was drawn to it. The same fate befell the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi and quatrains of Khayyam. Apparently Shahnameh was the story of Zoroastrians and Khayyam’s quatrains were tinged with opposition to religion.

The question is who our audience is now that the royal courts, Sufi centres and schools no longer exist. If we do not replace them with new institutions, the moral vacuum will be painful in the future. The audience for our literature should come from the educated layers. Unfortunately, the universities and schools do not perform their pertaining duties. We are currently bearing witness to a crisis among the audience of our literature. Then we can ask if the Ministry of Information and Culture, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Higher Education have made the necessary impact. Are the media interested in literature? Has the government had a strategic plan in the cultural field? … In my opinion, the answer is no to all those questions.

Our government and statesmen who replaced the old institutions do not recognise literature and arts at all. One glance at the programmes of presidential candidates would clearly show that there is nothing about culture and arts. Any reference to culture was geared to education, which is something else nowadays. This disorderly situation has caused us to have a poor cultural and artistic domain and a low number of enthusiasts for literature. That is not an incident. A dangerous intentional procedure contributed to it, because arts and literature give birth to thought and idea. Works of writers such as Boccaccio and Cervantes moved Europe and awakened it from the long sleep of the mediaeval ages.

The functioning of literature is a serious danger for corrupt, baseless and idle governments and irresponsible statesmen. Therefore those governments fear the promotion of literary culture among the people. They prefer to be indifferent to it. On the other hand, the states that have military and political presence in our country fear the emergence of thought and idea among out people. That is why they have not made any investment in the progress of culture and literature in the past 10 years. To the contrary, they have tried to engage our people with deceptive and entertaining programmes and to drug our young people with colourful sorcery. They have already done that in their own and other lands. Hollywood and Bollywood are clear examples of this. They scream that Afghanistan should be turned into a centre of commerce in the region, but nobody ever says that this land with its great and brilliant cultural legacy should be made into a cultural focal point in the region.

We have literary persons who do creative work. They do what they can even in the absence of prizes. Many of them publish their own works. The absence of publishers is another catastrophe.

Zaryab went on: Books and book reading must be in crisis. What else is to be expected, where the knowledge of several thousand years has been sent to oblivion; where knowledge, philosophy and literature have been replaced by superficial learning of computer skills and the English language? Here the black sorcery of Hollywood and Bollywood have drugged the minds of the people and the young people in particular; who would wish to read Dostoyevsky, James Joyce, Hedayat and others? The need for arts and literature is not even felt. Temples of big capital need tradesmen and merchants.

The third speaker, Mr. Jalal Nurani, said: In our country, writing is not a profession yet, because they never earned from this profession. They do not have an audience either. But writers live from writing in many countries. Our audience is also oppressed, because there are no writers to provide them with what they are seeking. This is one of our greatest challenges. For instance, we do not have literary critics. People watch films, photo exhibitions… but there are no critics to tell them the points of strength and weakness of those works. Most directors write their own scripts. When we ask them the reason, they say: Where are the script writers?

The moderator said: On the one hand, there is a need for the government to intervene in some areas of publishing. On the other hand, there are concerns about the revival of censorship. How real is that problem?

Mr. Nurani answered: The censors were active under the previous regimes. Today the Ministry of Information and Culture has abolished it, to avoid accusations of censorship. On the whole, our writers suffer from absence of audience and the people from lack of sufficient writers.

Mr. Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi, the last speaker, criticised the title of the public debate asking: Can we not say the crisis of audience, the crisis of writers, the crisis of publishing, crisis, crisis, crisis!?

He went on: Books published in the 1970s are being sold now. Did they not have readers? We have been facing the crisis of audience for a long time. The other big challenge is the challenge of publishing. The publisher is an intermediary between the writer and the reader. Do we have publishers in this sense in Afghanistan? The cost of publishing a book in Afghanistan is half the cost in Iran. The print-run is the same in the two Persian-speaking countries, but the publishing industry in the two countries is not comparable. We do not have distributors in Afghanistan. The writers hand out their books as presents. The other problem is the level of literacy despite the little progress in the past few years. One of the writers whose works I knew before sent me a book. When I read it, I noted that it was very superficial and told him so. He said: “That is the level of knowledge in Afghanistan.”

He continued: “The various organisations do not have a proper attitude to books. Most of them store the books and do not distribute them. We were given seven books as presents today. Is this correct? Will this solve the crisis or worsen it? I wish they had prices and I would choose by the price. Do the people attend to the food of soul as much as they attend to the food for body? I agree with Mr. Nurani that I can’t even call myself a writer, because I have not lived from writing. We do not have literary journalists.

In the question and answer part of the public debate, Ms. Dupree responded to the moderator’s comments on foreign aid, especially from the US. She said: That is completely true. We should have thought about cultural development more than economic infrastructure. I always viewed this issue critically. I wish the donors will also pay attention to it.

One of the participants addressed Mr. Nurani: If you make a comparison between a vulgar film seller’s shop and a library, you will notice that the young people take more interest in the films than the books. What has the Ministry of Culture done to deal with this situation?

Mr. Nurani answered: The ministry was divided into five ministries with five ministers in the past. That does not justify the fact that the ministry has done little. There are films that are worse than drugs. In the past we had seminars too. The ministry has resumed those programmes to find a pretext for publication of some books.

66th Goftegu Public Debate: Books with no readers, readers with no writers: what to do with the book crisis?